Aaron Lansky’s decades-long quest to save and preserve Yiddish books began, appropriately enough, with a book.

A lawyer’s son from New Bedford, Mass., he was selling drinks from a pushcart in a Boston square at the time. He was studying Yiddish at nearby Hampshire College, despite having been expelled from Hebrew school for hitting a teacher with a snowball. It was 1976, the U.S. bicentennial, and crowds were thronging the home of Paul Revere. While trying to figure out where his degree could take him, he hit upon a scheme to sell fresh-squeezed orange juice to the tourists.

As it turned out, few of them were interested in his OJ.

“Business was bad that summer,” Lansky writes in his 2004 memoir, Outwitting History: The Amazing Adventures of a Man Who Rescued A Million Yiddish Books, “but reading was good.”

A friend wandered by and handed him a book by McGill professor Ruth Wisse, BA’57, PhD’69, with an irresistible title: The Schlemiel As Modern Hero.

Schlemiels were familiar territory. Yiddish stories, not to mention Borscht Belt routines, classic sitcoms and Woody Allen movies, are replete with the archetypal born loser, who was nobody’s idea of a hero until Wisse recast the role: The schlemiel’s heroism lies in his very marginality, a representation of historic Jewish powerlessness whose outsider status allows him to question the dominant norms.

The failed orange juice squeezer was transfixed, and then transformed. “I sat down,” Lansky recalls from his home in Stockbridge, Mass., “started reading it, and that was it for fruit juice. By the end of the day, I knew this was the person I wanted to study with.”

Now 68, Lansky is entering his final year as president of the Yiddish Book Center, a multifaceted museum, library, bookshop, research network and cultural centre in Amherst, Mass., initially created out of his determination to salvage the precious books of Yiddish speakers – he and his colleagues have rescued 1.5 million volumes so far – that were being tossed out by those to whom they meant nothing.

When he came to McGill in 1977 to pursue his master’s degree in the newly established program of East European Jewish studies, finding assigned texts was problematic.

“There were only four or five students in the course,” he remembers, “but one would race to the McGill Library and one went to the Jewish Public Library and that was it. Everyone else had to go to Jewish neighbourhoods and knock on doors. People wouldn’t just give you a book. They’d sit you down, give you hot tea in a glass, and ask you what you thought of it. It was an experience only Montreal could offer, and it made the program quite special.”

The Yiddish culture Lansky knew was disappearing – his grandparents’ generation spoke Yiddish, but their children were eager to assimilate and move on from a language that loudly proclaimed its foreignness as a hybrid Germanic vernacular, written in Hebrew script. Dusty books depicting village characters disappeared into dumpsters.

Scholars at the time were concerned. Some estimated that only 70,000 or so volumes could be recovered. Yiddish books were thought to be in serious peril.

Lansky took pleasure in the plain-speaking truth-telling misfits of traditional Yiddish literature – and the mischievous humour that informed so many of the stories didn’t hurt.

In Montreal, to his delight, Yiddish remained a living language.

“It was probably one of the last cities in the world where Yiddish was widely spoken within the Jewish community, not just by old people but by the Canadian-born generation, to whom it was passed primarily through the Jewish day schools.”

He was recruited to teach children Yiddish, and became a regular at the Jewish Public Library, one of a host of institutions that immigrant Jews created to serve their community. He lived in Snowden, two blocks from the library, and realized that when he sat down to work, interruption was inevitable.

“Older Jews would come over to kibbitz and ask me what I was doing. For the most part that was my Montreal social life. To sit alone and study quietly? I don’t think that was culturally possible.”

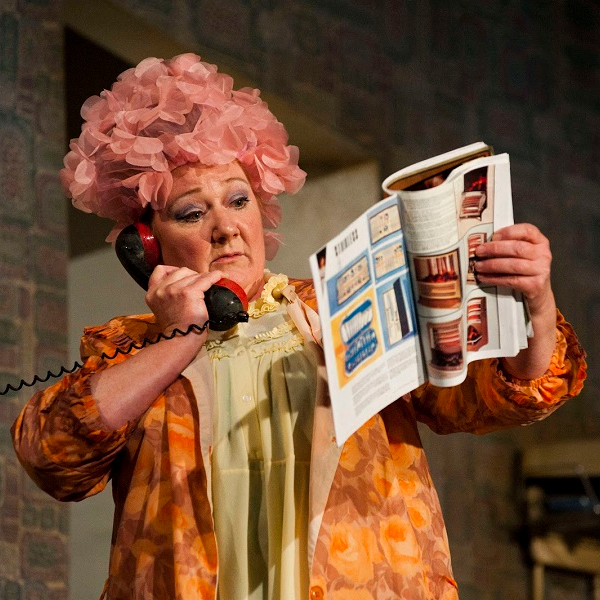

Aaron Lansky, founder and president of the Yiddish Book Center

Every Saturday night – “This will reveal a little too much about myself, I’m afraid” – Lansky headed to the library for Yiddish lectures and found the building packed. He wasn’t entirely surprised that Yiddish literature could exhibit such a pull: Veneration of books was a distinct trait of Jewish society.

“Jews were a very bookish people,” he says, “largely because without a country of their own [for so long], books became their portable homeland, the repository of their culture, history and identity.” Even in his own home, when a book fell on the floor, “we’d pick it up and kiss it. It was what we were conditioned to do.” So, when he started hearing stories about Yiddish books being trashed as readers died off and once-vibrant cultural institutions shut down, he was incredulous. And he decided to act.

He put out the word that he’d welcome Yiddish books, thinking mainly of himself and his McGill colleagues. He was inundated, and transitioned from bike to moped to station wagon to rental van as pick-ups multiplied. His apartment became a warehouse, and he slept in a hammock to increase floor space. Back in New Bedford, where he’d developed a parallel rescue scheme, his parents had had enough: Their second floor was in danger of collapse.

Pondering the chaos he’d created, Lansky had his life-changing realization: He would save all the books he could before it was too late.

Very slowly and not so surely, propelled by the energy of similarly inspired friends and a network of Yiddish-loving book haulers, he created a vigorous, forward-facing organization that became the Yiddish Book Center. It wasn’t easy: His shoulders gave way after years of toting 30-kilo boxes down tenement stairs. But his zeal paid off: In 2014, the center was honoured at the White House as a landmark cultural institution.

“All things are possible,” U.S. First Lady Michelle Obama told him when he remarked that his Yiddish-speaking grandmother could not have dreamed of that moment.

The guiding mission of the center has shifted from rescuing books to digitizing them and putting them online – with five million downloads so far. Translation of Yiddish works is also a priority, a project funded initially by Steven Spielberg.

“It’s the only way to make the literature widely accessible,” says Lansky. “Just two per cent of Yiddish literature has been translated so far, and a lot of that was done immediately after the Second World War and tended to be the schmaltzier books, that showed the world in softer focus. Books about revolution, class conflict, books by women and what we would call transgressive literature were overlooked.”

And those lectures Lansky used to attend at the Jewish Public Library? It turns out that behind the scenes, someone was busily recording them on a reel-to-reel tape recorder – the instinct to preserve Yiddish culture was already present. The Yiddish Book Center’s technicians have remastered the tapes and digitized them so they can be heard more widely online – “some of them are breathtakingly good,” he says appreciatively.

And thus, Aaron Lansky’s transformation is complete: His Montreal Saturday night social life has become a precious cultural treasure.