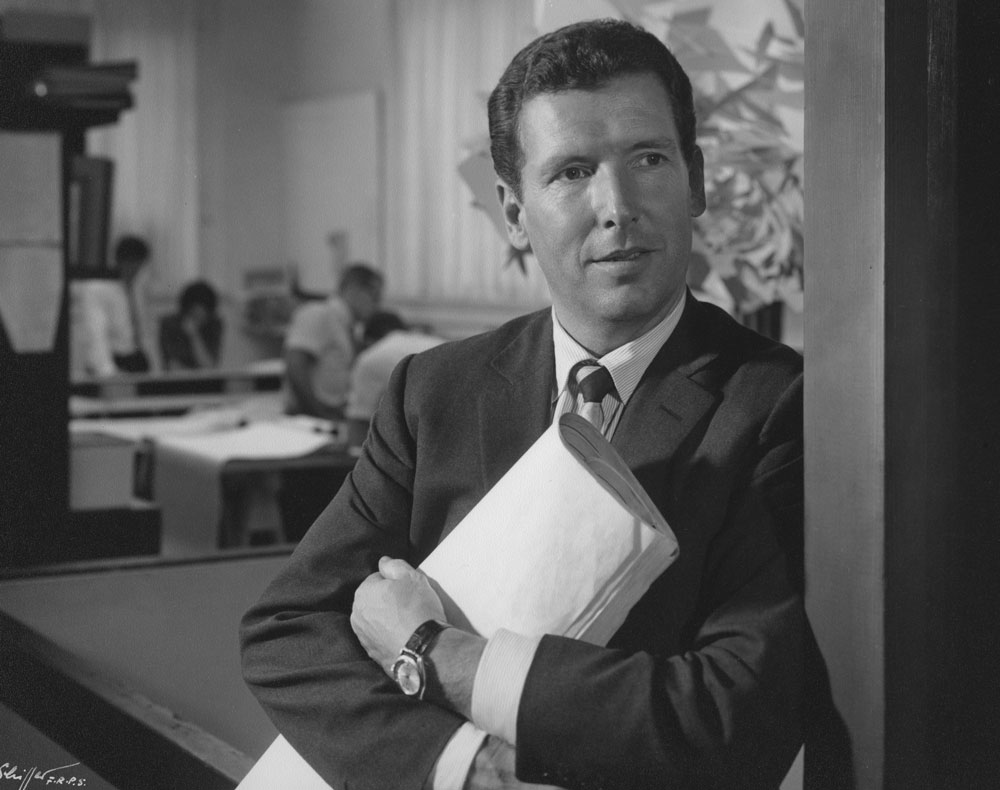

A century after his birth, one of Canada’s most influential architects is finally getting his due.

That isn’t to say that Arthur Erickson, BArch’50, LLD’75, was ever lacking in recognition. But after a difficult final act in his career, one that saw him bankrupted and stripped of his licence to practice, Erickson is once again being celebrated for his groundbreaking work.

When Erickson died in 2009, just shy of his 85th birthday, McGill associate professor of architecture David Covo, BSc(Arch)’71, BArch’74, described him as “Canada’s most celebrated architect [and] our unofficial Architect Laureate.”

At the height of his career, Erickson was as close to a celebrity as a Canadian architect had become, mingling with Hollywood stars, sailing with Pierre Elliott Trudeau and holidaying in a spectacular house on Fire Island that Erickson built for himself and his partner, interior designer Francisco Kripacz.

Erickson’s impressive body of work — including the University of British Columbia’s Museum of Anthropology, Simon Fraser University, the University of Lethbridge, Toronto’s Roy Thomson Hall, and the Canadian Embassy in Washington, DC — earned him the American Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal in 1986, upon which renowned U.S. architect Philip Johnson praised Erickson as “by far the greatest architect in Canada” and “perhaps the greatest on this continent.”

But in many ways Erickson’s legacy has been oddly overlooked. “He was a genius. But today his work is not that well known outside of Vancouver,” says Covo.

Influenced by his travels

Covo has set out to change that. Over the past decade, he has been leading research into Erickson’s vast archives, building an index of more than 800 projects around the world and tracing Erickson’s vast influence, which includes what Covo describes as “the alumni” of around 400 architects and designers who worked for him.

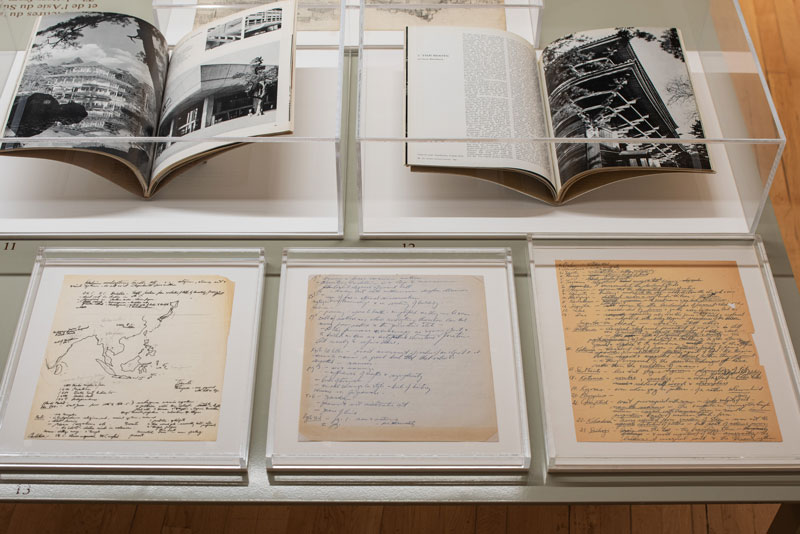

Covo’s latest effort is Being There: Photography in Arthur Erickson’s Early Travel Diaries, an exhibition currently on display at Montreal’s Canadian Centre for Architecture. The exhibition explores how Erickson’s global travels — especially a research trip to Japan — shaped his approach to architecture.

Most of this was documented not in sketches or journals but in photographs, on 8mm film and in handwritten letters sent to his mother, which she typed up and sent to friends such as Gordon Webber, one of Erickson’s architecture professors at McGill.

“He sent [the letters] to her first because nobody else could read his handwriting,” says Covo. Erickson was “building up source material,” Covo notes, by cataloguing ideas and observations that later ended up — “sometimes almost verbatim” — in articles, speeches and monographs.

Born in Vancouver in 1924, Erickson developed an early interest in painting. His father suggested that architecture might be a more practical career, and at the age of 17, Erickson happened to meet renowned Austrian modernist Richard Neutra at the home of Vancouver painter Bert Binning.

Neutra told him the best path to becoming a good architect was to study engineering at MIT. That held little appeal for the artistically inclined Erickson. “I said, ‘Well that finishes architecture, as far as I’m concerned,’” he later told the McGill News.

“He was a master of site. He would take a space and design a building that felt like it already existed in it and would always exist in it.”

Danny Berish, co-director of Arthur Erickson: Beauty Between the Lines

Instead, at the beginning of World War II, Erickson signed up for the Canadian Army Intelligence Corps and studied Japanese language and culture before being deployed to work in India, Ceylon and British Malaya.

He intended to join the diplomatic corps after the war. But when he visited Arizona and experienced Taliesin West, a home and studio built by the legendary architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1937 — today listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site — Erickson was persuaded to finally take his father’s advice and study architecture.

After graduating from McGill, he won a $1,500 travel scholarship and, combined with his veteran’s allowance, used it to pay for a two-and-a-half-year journey around the Mediterranean. After a stint in London, where he worked for the son of Sigmund Freud, Erickson returned to Vancouver, where he spent several years teaching and designing increasingly ambitious houses.

By the time he travelled to Japan in 1961, funded by a grant from the Canada Council for the Arts, he already had a sense of what to expect; he was interested in the meditative Japanese approach to space and the country’s long history of woodcraft. “The trip confirmed his intuition,” says Covo. And being able to experience first-hand the Japanese art, architecture and culture he had long admired transformed the way Erickson approached architecture.

Together with his earlier explorations of classical architecture around the Mediterranean, not to mention his fascination with the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright — himself influenced by Japan — Erickson’s trip to Asia gave him a new appreciation for material simplicity and the way a building’s relationship to landscape could shape a person’s emotional experience of architecture.

“He was always designing to be in harmony with nature,” says Danny Berish, co-director of Arthur Erickson: Beauty Between the Lines, a feature-length documentary that was recently screened at the Vancouver International Film Festival. “He was a master of site,” says Berish. “He would take a space and design a building that felt like it already existed in it and would always exist in it.”

Erickson’s breakout project was the new campus for Simon Fraser University, designed with architect Geoffrey Massey, which was completed in 1965. It is an amalgam of the lessons Erickson learned on his travels, with a low-slung concrete quadrangle arranged around a courtyard that evoked Al-Azhar University in Cairo, with reflecting ponds inspired by historic Japanese architecture as well as the work of modern master Kenzo Tange.

Jet-set architect

Simon Fraser was followed by a string of successes, both in Canada and abroad. By the 1980s, when an economic downturn gripped North America, Erickson shifted his focus to the Middle East and Asia. As a firm believer that architects needed to fully experience the location of a project in order to design for it — sometimes he would even sleep on site — Erickson spent much of his time in the air. So much, in fact, that he once appeared in an advertisement for Air Canada’s frequent flyer programme.

Erickson’s jet-set lifestyle extended beyond work: he maintained residences in Vancouver, Los Angeles, Toronto and New York, and was known for the lavish parties he threw with Kripacz, who Erickson hired after his furniture design studio went bankrupt.

By 1992, Erickson and his firm had suffered the same fate. He lost everything — including his architect’s licence — but was able to continue living in the Vancouver house he had designed thanks to its purchase by a non-profit foundation set up by supportive friends.

All of this made the news, but otherwise, Erickson kept his home life closely guarded.

“Arthur really did keep those two worlds really very separate, the personal and professional,” says Berish. “But his personal life informed his professional life. You could see that a lot in his work.” That was especially true of his relationship with Kripacz, whose vivacious design sensibility influenced many of Erickson’s projects.

Despite his financial struggles, Erickson managed to continue working as a design consultant. His later works include the light-filled Waterfall Building in Vancouver, designed in 1996 and completed in 2001. The following year, he was hired to design the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, which is centred around a dramatic cone-shaped hot shop where glassblowers work, its form inspired by so-called “beehive burners” that once stood on the city’s waterfront. It opened in 2002.

The centenary of Erickson’s birth has sparked a new surge of interest in his work and life. Along with Being There and Beauty Between the Lines, there was another exhibition in Vancouver, a lecture series, and a Vancouver International Film Festival programme of movies that featured Erickson’s buildings. (The films included Intersection, in which Richard Gere played a character inspired by Erickson; the architect’s real-life models and drawings were used in the movie.)

According to Covo, there’s still an enormous amount of material to explore. “He threw nothing out,” Covo says. Delving into Erickson’s archives, which are housed in many locations including McGill, “you feel a bit like a miner. You see a vein and ask, ‘Is that gold?’ What we’re doing now is just the beginning.”