When Georges Drolet, BSc(Arch)’83, BArch’85, was studying architecture at McGill, his parents would occasionally come to visit from Quebec City and treat him to a special lunch on the ninth floor of Eaton’s department store. That’s where Île-de-France was located – an extraordinary 500-seat Art Deco restaurant that opened in 1931 with a design by prominent French architect Jacques Carlu.

“It was a kind of magical place,” says Drolet. The restaurant’s lavish interior was inspired by the ballroom of the French luxury ocean liner Île-de-France, which Lady Flora Eaton had fallen in love with on a trans-Atlantic voyage. The restaurant was initially a buzzy destination for well-to-do Montrealers before becoming a beloved and seemingly timeless local institution.

When Eaton’s went bankrupt in 1999, however, the restaurant was shuttered. But it was certainly not forgotten.

“It’s rare for a commercial space to remain in people’s memories like that,” says Drolet. In 2000, Quebec’s Ministry of Culture listed the restaurant as a historic monument. Drolet and his architecture firm, EVOQ, were enlisted to develop a conservation plan for the space. Everything was protected, right down to the tableware. But the new owners of Eaton’s could never figure out how to reopen the restaurant in a way that made financial sense.

“It was a kind of magical place.”

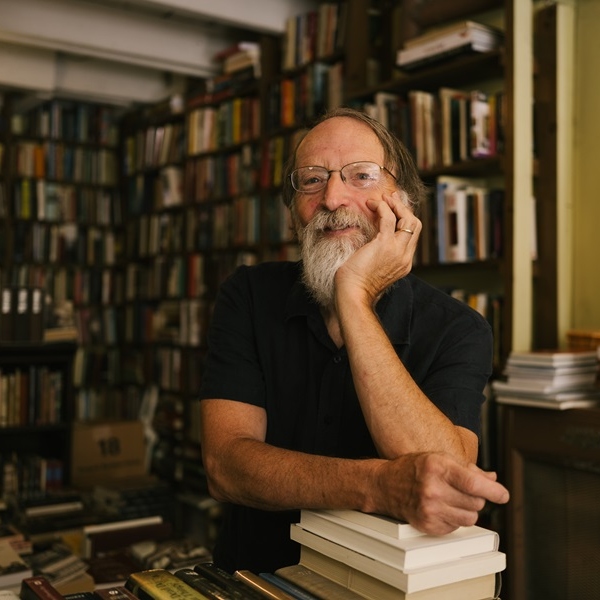

Georges Drolet, architect

Until now. Four decades after Drolet first dined there with his parents, he and his team have transformed the historic space into Le 9e, a restaurant and event space that will finally reopen the beloved space to the public after 25 years. “When I was a student, I never could have imagined I’d be doing this so many years later,” he says.

He might not have been able to foresee this particular project, but it was always Drolet’s plan to be an architect.

“I was eight years old when I decided to become an architect,” he says. He credits a visit to Expo’67 with sparking his interest in built environments and his desire to move to Montreal.

While he was studying at McGill, he met EVOQ co-founder Julia Gersovitz, BSc(Arch)’75, BArch’75, a pioneering conservation architect who taught at the University. Fascinated by the possibility of giving old buildings new life, Drolet followed in her path after graduation.

In the 1980s, architectural conservation was in its infancy as a profession, coming on the heels of the historic preservation movement that opposed the widespread demolition of old buildings in many cities around the world.

“When I started, it was right between the activist period – people chaining themselves to bulldozers – and the start of the professionalization of conservation,” says Drolet.

A big part of conservation has to do with restoring historic spaces and materials to their original glory. But an even bigger part involves rethinking old buildings to make them useful now and in the future.

“That’s a really exciting challenge because you can’t only have museums,” says Drolet. That means making critical decisions about how to adapt and reuse historic structures in a way that brings them up to date without sacrificing what made them valuable in the first place.

One of Drolet’s most recent projects is an example of that. In the east end of Montreal, the Bibliothèque Maisonneuve is an ornate Beaux-Arts structure that originally served as the city hall of Maisonneuve, a master-planned industrial town. The library needed to be renovated and expanded, so the team of architects decided to add two airy, glassy wings that are slightly set back from the original structure.

The division between old and new is clear, but visitors now have a chance to appreciate the details of the historic building up close in a way that wasn’t possible before.

By contrast, visitors to Le 9e will discover a space that looks very much like the one they remember – despite substantial changes.

The iconic main hall was too large to operate as a restaurant in today’s market, so it will be reserved for events. The enormous kitchen needed to be rethought, asbestos removed from the walls, and the whole floor brought up to modern safety and building codes.

“We had to be very selective and clever about where to make openings to go into these hidden spaces,” says Drolet. “Everything that required the most effort to reopen is completely invisible.”

Drolet is certain the restored restaurant will offer a nostalgic experience for many customers. “I’d like to be there hovering around when people come in again, hearing what they have to say,” he says. “But now it’s also open to new memories.”