Adam Gopnik’s new book on liberalism begins with U.S. president Donald Trump’s stunning electoral victory in 2016, as the author tried to comfort his daughter (in high school at the time) who was shocked and upset by the result.

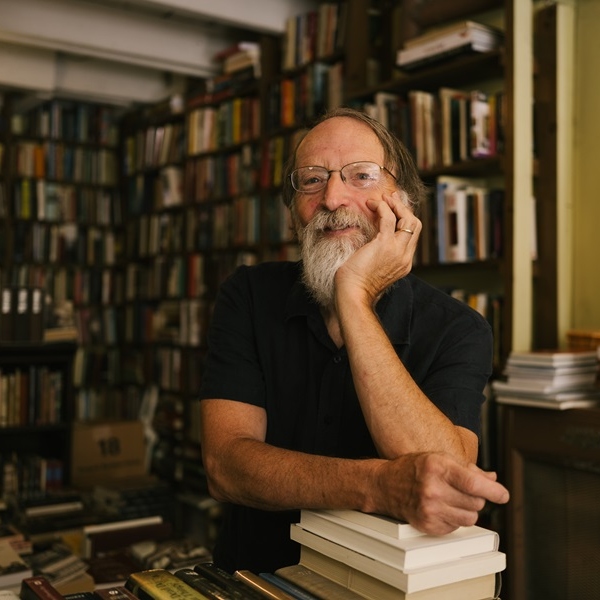

“I set about writing this as a kind of long letter to her and to her generation about what I felt liberal humanist values were,” says Gopnik, BA’80, DLitt’13, a staff writer at The New Yorker.

In A Thousand Small Sanities, Gopnik delves back in time to explore liberalism – what it means, why it comes under attack from both the right and the left, and why, in his view, it’s “one of the great moral adventures in human history.”

That’s because its consequences have been so salutary, Gopnik said in an interview. “Because liberal societies have created, what I would say without apology or quaver, are the most prosperous and broadly pluralist [societies] that mankind has ever seen.”

He rarely mentions Trump by name in the book – including in the opening chapter – although there’s no mistaking who he means in a reference to ‘one petulant autocrat.’ While the spectre of the Trump presidency overhangs the book, Gopnik says he didn’t want to write specifically about Trump or Trumpism. For starters, he already does that in The New Yorker.

“It’s a long essay on liberalism. And I didn’t want it either to be dated by having too much current politics in it, nor to be too polemical in arguing about current personalities too much,” Gopnik says. “So I deliberately displaced it from the contemporary context and made it much more rooted in older history.”

He also wanted to expose his daughter and her generation to figures like philosopher John Stuart Mill, civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, the main organizer of the March on Washington in 1963, and 19th century reformers Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine and Robert Baldwin, who forged a historic partnership in what was then the “Province of Canada”.

The liberal tradition he references and defends in the book begins in the middle of the 19th century. “It’s really the inheritance of John Stuart Mill and [writer and women’s rights advocate] Harriet Taylor,” he says, of the couple who married after Taylor’s first husband died. “That’s why I begin the book with them. And it’s that particular legacy that believes equally in egalitarian reform and in individual liberty. It believes in both with equal passion. That’s where liberalism begins for me and that’s the political tradition that I’m talking about.”

One of his ambitions for the book was to “model the liberal temperament” on every page. “I tried…to be extremely fair to all the people I’m arguing with, to summarize their arguments as sympathetically as I possibly could,” Gopnik says.

“I wanted to model liberal tolerance on the page as a style of argument as much as I wanted to sum up liberal arguments.”

The liberal tradition is in danger, according to Gopnik, who writes about being kept awake at night by the thought that liberal cities and liberal civilization could vanish and the values built there, eliminated.

Are things that dire for liberalism? Gopnik says he believes the threat is real and notes that when he talks about liberalism, their form is liberal institutions, such as freedom of speech, freedom of the press, the oscillation of parties in power, and the liberal university, which is probably the central institution.

“They are all under attack all of the time…much less in Canada, but certainly in America and throughout Europe, they are under assault from the right wing, particularly here in America, but also from leftists in France and in England.”

Gopnik says he hopes the book will act as a reminder not just to his daughter’s generation, but to others more broadly that liberal institutions “are extremely rare historically, extremely fragile and absolutely vital.” They need to be defended.

His prescription for liberalism? It needs to “reappear in its truer colors as public-minded, patriotic, and passionate,” he suggests in the book.

“There is no more important piece of public-mindedness that liberalism needs to recommit to than public education,” writes Gopnik, noting its close association to nearly all the social advances that liberals take credit for. Moreover, “a vast social investment in early education is the best weapon against inequality and class stratification.”

Asked in early May which of the candidates vying for the Democratic Party presidential nomination impresses him the most, Gopnik mentioned having the chance to sit in on a fundraiser for Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana.

“I was hugely impressed by how smart he was and also by his instinct that you had to address the democratic deficit in the United States. The failure of things like the Electoral College and gerrymandering and so on, before you could even begin to have significant social change.”

But being a liberal, Gopnik adds, means he has no Utopian hopes. “I don’t imagine that there’s a messianic figure out there who will suddenly magically solve our problems. I am more than content with good enough when I’m looking at much too bad.”