Oyez, oyez! Take the survey of Canadian English!

Wait… Who says “oyez” anymore? Come to think of it, does anyone still say, “chesterfield,” that uniquely Canadian word? Do we rhyme “drama” with “gamma,” or are we slipping into a “comma”-like pronunciation? What’s the status of “zed” these days?

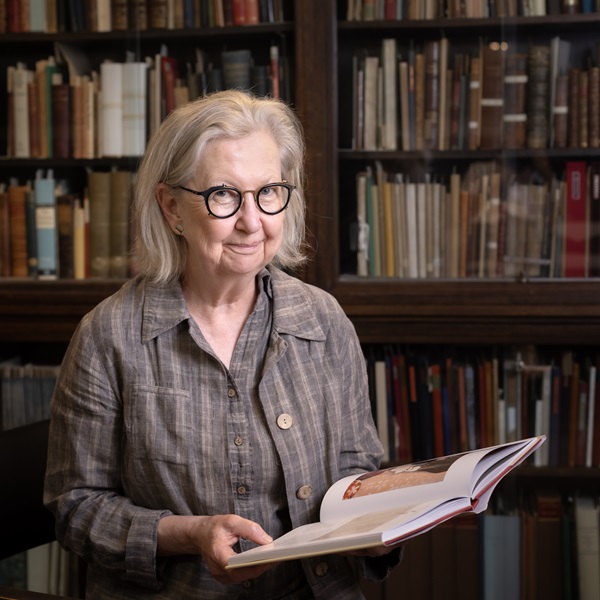

McGill associate professor of linguistics Charles Boberg has launched an online survey to gauge how Canada speaks English. He was inspired by the 50th anniversary of The Survey of Canadian English done by researchers from the University of Victoria. Their 1972 report gleaned info from more than 14,000 grade nine students and their parents.

Boberg chose many of the same multiple-choice questions and added a few new ones to the mix. He ditched dated questions like asking if you call money “bread,” or if you rhyme “home” with “dome” or “dumb.” “No one would say, ‘I’m going hum’ now,” Boberg says of the old variant.

But he kept the one about the couch/sofa/whatever you call it. In 1972, 83 per cent of parents used the word “chesterfield,” but only 66 per cent of their teens did. Did those teens grow up and revert to their parents’ ways of speaking, or has chesterfield been abandoned on the trash heap of forgotten terms? Just as parents model language to toddlers, kids can influence adults too (as anyone over 40 who has ever said “rizz” can attest).

Survey participants will be asked if they say “Lootenant” or “Leftenant,” whether “missile” rhymes with “thistle” or “misfile.” And don’t worry, if you’re a waffler you can reply, “either way.” (And speaking of “either,” do you say the “ei” like “bide” or “beet”?)

You’ll be given six choices for what you dub a pizza flourished with myriad tasty ingredients, and seven for that double-shoulder-strapped item that students use to hold their books.

“Funny thing is, these are not particularly Canadian [spellings], they’re British, but Canadians go on about them.”

Charles Boberg

As for “zed,” Boberg suspects “zee” is ascendant. Maybe because we talk of Gen Zee? But Boberg believes Canadian spelling choices like “centre” and colour-with-a-U have increased. “Funny thing is, these are not particularly Canadian, they’re British, but Canadians go on about them.” The British spelling is borrowed from the French word couleur. In Latin, it’s “color,” Spanish, “color,” Italian, “colore,” he says. “It’s just the French who did something with that final vowel and that got into English.” That means O-only Americans are more faithful to the word’s Latin origin.

Boberg’s own research on Canadian English suggests six main regions: B.C., the Prairies, Ontario, Quebec, the Maritimes, and Newfoundland, with various subregions. Tracing our country’s anglo accents is to trace the history of migration.

Canada has far fewer regional variations than Britain, but more than Australia, “where differences are social rather than regional,” notes Boberg. “Canada is perhaps more socially uniform.”

Newfoundland’s distinct accent is due to late 18th century migrants from southeastern Ireland and southwestern England. Nova Scotia attracted Scots and post-revolutionary Loyalists fleeing America. Loyalists also populated New Brunswick (along with Irish), though most Loyalists who came to Quebec moved on to settle in Ontario. Montreal’s 19th century port capacity attracted direct immigration from Britain and Ireland.

Ontario also drew many British and Irish. Those from Ulster tended to settle in the rural areas, while Catholic Irish labourers instead flocked to large industrial centres. When the railway connected the coasts, Ontarians rode west, bringing their ways and accents with them. They were joined by Brits and many kinds of Europeans – Germans, Ukrainians, Scandinavians.

Though the survey analysis will focus on native English speakers in Canada who are representative of where they grew up, everyone is welcome to participate. “American data are valuable because it allows us to see what’s unique about Canada,” says Boberg.

To take part in the survey, visit www.mcgill.ca/canadianenglish