A living legend

Brenda Milner first arrived in Montreal in the fall of 1944 alongside Peter Milner, her new husband. Peter was a physicist (he would later distinguish himself as a neuroscientist after making a career shift) recruited to help Canada’s nascent efforts in atomic energy. It wasn’t meant to be a long stay.

“We thought we were coming for one year – and now eight decades have elapsed,” says Milner, PhD’52, DSc’91. An experimental psychologist, she had been busy assisting Britain’s Second World War efforts, using aptitude tests to help determine who might be the best candidates to become fighter pilots or bomber pilots.

“It was a dramatic moment in a turbulent time, but nonetheless I was very excited,” says Milner of the move to Montreal. “My enthusiasm had little to do with Peter’s involvement with Atomic Energy Canada, but was entirely due to the fact that I had arrived in a French-speaking city.” Milner’s mother had taught her French when she was young, sparking a lifelong enthusiasm for the language.

In Montreal, she initially struggled to find work, despite graduating with a “starred first” from Cambridge – the highest mark possible on her final exams, and a rare achievement. “I was very surprised, indeed taken aback, that people [in her new city] did not understand the worth” of such an accomplishment, says Milner.

She did encounter one individual who was familiar enough with European universities to be impressed – Father Noël Mailloux, “a tall medieval, picturesque, Dominican bedecked in long white robes,” says Milner. He was the founder of the Institut de psychologie at the Université de Montréal, and Milner went on to teach there for seven years.

She would switch to McGill for her doctoral studies – and would take on a historic research project for The Neuro (the Montreal Neurological Institute – Hospital) that would radically alter what the world understood about how memory functions.

Her now famous experiments involved Henry Molaison, a patient who had no ability to form new long-term memories. He never remembered Milner’s name, though the two worked together for decades. Even so, Milner managed to prove that Molaison was capable of learning new skills and improving in them with practice – and in the process, she established that there were multiple memory systems and not one singular pathway.

She would go on to work on other groundbreaking studies, helping to identify the brain regions involved in language, bilingualism and spatial memory. And she would win several major awards in the process, including the Kavli Prize in Neuroscience, the Gairdner Foundation International Award in Health Research, and the Quebec government’s Prix Wilder-Penfield.

She had the chance to work closely with the legendary Penfield, a pioneering neurosurgeon and the driving force behind the creation of The Neuro, in the early stages of her McGill career.

“Going into the operating theatre and watching Penfield stimulate the patients’ cortex was a privilege,” says Milner. “For me, the fact that [surgeons stimulating the brain] could evoke memories was startling.”

Milner has remained at The Neuro for decades. Was she ever tempted to go anywhere else?

“I could have gone to MIT, but I did not feel American,” she says. “When it comes right down to it, I have always been too happy to leave this great bilingual city. French was a very powerful magnet.”

Over the years, she has played a key role in training dozens of talented graduate students and postdocs – some of them, like Michael Petrides, Denise Klein, Robert Zatorre and Julien Doyon, PhD’88, have stayed at The Neuro and built impressive careers of their own. The Neuro has consistently given its researchers access to the most advanced technologies and techniques available at the time, but Milner thinks the attachment that people have for the place goes deeper than that.

“There was and is a definite family feeling [here] that likely emanates from Penfield,” says Milner.

The 103-year-old has witnessed a lot of change in her city – from the era of street cars, to the arrival of the Metro, to, soon, the launch of the light-rail train system – and she misses some of the things that Montreal has lost along the way.

“The loss of the [Montreal World Film Festival] was an emotional shock. I thoroughly enjoyed going to as many movies as possible. Many of my favourite restaurants – Vent Vert, Molivos, Le Mas des Oliviers – have come and gone.

“The most dramatic event was the [1998] ice storm,” says Milner, when asked if any periods of Montreal history stand out to her. “I was at the Ritz for a couple of days because we lost power in my apartment. All the dogs were kept in the lobby.

“My favorite period has always been now,” she adds, “but the world is not at its best. COVID should worry me, but it does not. I have been double vaccinated and eagerly await the booster shot,” she said last fall. “I believe in science.”

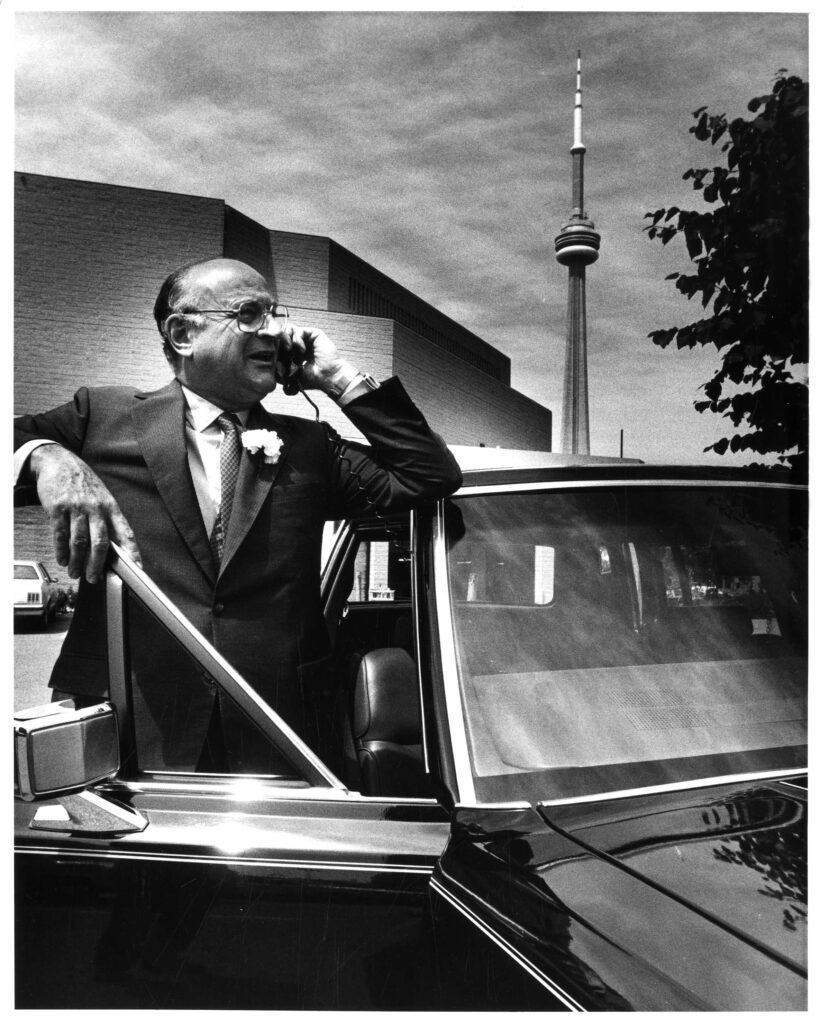

The groundbreaking chancellor

Credit: Bell Archives

Over the course of his long career at Bell Canada Enterprises (BCE), Jean de Grandpré, BCL’43, LLD’81, became one of the Canadian business world’s towering figures. A Companion of the Order of Canada, a Commander of the Ordre de Montréal, and a member of the Canadian Business Hall of Fame, de Grandpré was the CEO in charge of BCE when it became the first Canadian company to make more than a billion dollars in profit.

If BCE has been one of the constants for much of his life – the 100-year-old still has an office there that he visited frequently before the pandemic – McGill would be another.

When he decided to study law at McGill in the early 1940s, it was unusual for French Quebecers to pursue law degrees at the University. He was one of only two francophones in his cohort at McGill.

“Up to that point, I had never had an English-speaking friend,” says de Grandpré. “I was living in a very French community, so there was never that opportunity. My brother [Louis-Philippe de Grandpré, BCL’38, LLD’72] had already gone to McGill and I wanted to be fully bilingual.”

He wasn’t quite sure what to expect. “My grammar in English was almost perfect, but my vocabulary was very thin. My accent was probably very poor. And within a month, I was elected to be the head of my class. The next year, I became the president of the [law students’ association].” De Grandpré says he was surprised by “the open-mindedness” of his fellow students, and by how welcoming they were.

“I was also fortunate to have extraordinary teachers at McGill. I had two or three judges from the Supreme Court [as teachers].”

That said, de Grandpré wasn’t a big fan of F. Cyril James, McGill’s principal at the time.

At one point, de Grandpré was part of a group of law students who launched a snowball attack against their counterparts in engineering.

“The engineering students outnumbered us by about six to one, but we were up on a hill, so we had the advantage of being in a higher spot. We were all throwing snowballs and, suddenly, F. Cyril James appears, and he decides he is going to go through the ‘no man’s land’. He thought we would all stop [hurling snowballs] because he was walking through.”

James was wrong.

“I was the president of the law students at the time and, along with the president of the engineering students, I was [ordered] to appear before Principal James and apologize profusely.” Decades later, de Grandpré still doesn’t have much sympathy for James’s outrage. “He was an uptight guy. If that had been David Johnston” – McGill’s principal from 1979 to 1994 and a man de Grandpré would come to know well – “he would have picked up some snow and joined the fight.”

A few years after graduating from McGill, de Grandpré would play a small but significant role in the most celebrated spy scandal in Canadian history.

Igor Gouzenko, a clerk with the Soviet Embassy in Ottawa, defected to Canada in 1945, carrying with him hundreds of documents related to a Canadian spy ring that was trying to feed state secrets to the Soviet Union. The principal member of the spy ring was Fred Rose, a Member of Parliament. Also implicated in the scandal was Raymond Boyer, BSc’30, PhD’33, an instructor in McGill’s Department of Chemistry.

De Grandpré was then a young lawyer working for a firm headed by Philippe Brais, BCL 1916. Brais, along with Gérald Fauteaux (one of de Grandpré’s teachers at McGill), was representing the Department of Justice in the case.

“All these guys who were operating with Fred Rose were using aliases,” explains de Grandpré. “They weren’t using their real names, they were using code names.” De Grandpré was assigned the task of going through all the documents and determining who was who, a role he likens to navigating his way through a maze. “It was making sure that the I’s were dotted, and the T’s were crossed properly.” The 63 code names that de Grandpré identified were later published in a Royal Commission report.

In the 1970s, de Grandpré joined McGill’s Board of Governors. He soon found himself at odds with many of his fellow governors. Robert Bell, McGill’s principal at the time, was championing the idea of moving much of Macdonald College’s activities downtown.

De Grandpré didn’t like the plan. So many of the key elements of Macdonald’s identity, to his mind, were firmly rooted in its location in Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue and the agricultural facilities there.

“It made no sense to me,” says de Grandpré. When the matter came to the board, “I was the only dissenting vote and I had just joined a few months before.” Most faculty at Macdonald strongly opposed the proposed move, as did the Macdonald Stewart Foundation (philanthropist Sir William Macdonald had been the driving force behind Mac’s creation), and the plan never came to pass.

“That’s why, at Macdonald, I’m like [a saint],” de Grandpré says with a laugh. It’s no coincidence, he adds, that an annual lecture series at Mac is named in his honour.

De Grandpré also has close ties to another part of McGill, The Neuro. He was the president of the Montreal Neurological Hospital Board from 1971 to 1977. He was a member of the Neuro Advisory Board from 2000 to 2015. And he and his family provided the support that led to the creation of the de Grandpré Communications Centre at The Neuro’s Brain Tumour Research Centre.

Years after voting against moving Macdonald Campus, de Grandpré would surprise McGill decision-makers once again. This time, the University had reached out with a remarkable offer. De Grandpré was asked to become McGill’s next chancellor. He would be the first francophone in McGill’s history to fill the role.

“I refused it!”

At the time, de Grandpré, then the CEO of Bell Canada, was embroiled in conflicts with the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) and the Liberal government of Pierre Trudeau (a former classmate at Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf) over his efforts to reorganize Bell, efforts that ultimately led to the creation of BCE.

“I had to fight the CRTC and the government in court. I didn’t think I should [become McGill’s chancellor] because I didn’t think I would have the time to do a good job.” But when he reported the overture from McGill to Bell’s board of directors – he was obligated to inform the board of any such offers – de Grandpré says he was strongly advised to reconsider his refusal.

“It was a ruckus. The directors said, ‘What! You refused that?!’ They thought it was good for the company to see its president become the chancellor of McGill and they promised to give me the support I would need to create BCE.”

De Grandpré enjoyed his time as McGill’s chancellor. His office at Bell was a short walk away from McGill’s downtown campus, and he fondly remembers his regular meetings with Principal David Johnston and Board Chair Hugh Hallward, BA’51, DLitt’92, as they dealt with the issues of the day over sandwiches and coffee.

One of the toughest parts of the job related to convocation.

“The three of us each took up a third of the names” of the degree recipients who would be called to the stage to receive their degrees, says de Grandpré, and with such a high proportion of McGill’s students coming from other countries, pronouncing some of those names correctly could be a challenge.

“I can remember sitting with [Johnston and Hallward], and we would be asking each other, ‘Do you know how to pronounce this one?’ Sometimes, we would get help from professors who had these students in their classes. We didn’t want to get it wrong. Even so, I’m sure some of the graduates did not recognize their names [when they were called].”

A soldier and a scholar

Flip through a copy of the 1940 Old McGill Yearbook and you’ll come across a photo of the McGill students who served on the executive of the Undergraduate Society that year. With their stylishly slicked back hair and their crisp suits and ties, they look quite dapper. Did they dress up special for that photo?

Robert Spencer, BA’41, one of the students in the picture (he was the group’s vice-president), says no.

“A [dress] shirt, tie and jacket were the expected clothing for regular classes in those days,” the 101-year-old says.

The McGill students of that era might have made a point of dressing well, but many were short on cash and otherwise led frugal lives. “In the late 1930s and early 1940s when I was at McGill, we were still coming out of the Depression and were into the [Second World War],” says Spencer.

Finances played a role in his decision to go to McGill.

“Attending any university outside of my native Montreal was not feasible,” says Spencer, adding that his father made it clear that Spencer would be responsible for paying his own way through university. He received a bursary from McGill, without which he wouldn’t have been able to afford his studies, as well as a small loan.

“I think the one thing that surprised me [the most about McGill] was the way I was drawn into the life of the University, as I was by nature shy and lacked self-confidence,” says Spencer. Aside from the Undergraduate Society, he also served as the athletics manager for the Faculty of Arts and Science, coaching its six-man rugby team. And he joined the staff of the McGill Daily, becoming a reporter and later an editor.

The Daily really was a daily back then, at least during weekdays. “It was a serious newspaper,” recalls Spencer. “We worked to a tight deadline overnight and by the time the University opened in the morning, the paper was by the door.”

Spencer says the war, in its early days, didn’t immediately cast a dark shadow on student life at McGill – though that would change.

“I was not yet 19 and just about to enter my third year at McGill when the German Wehrmacht drove into Poland in September 1939,” says Spencer. “I think we did not really comprehend what this invasion meant nor what lay ahead. The [military] didn’t want students at that time. We were encouraged to stay put and to complete our studies before becoming involved in the war effort as we were deemed to be more valuable to the cause as graduates.”

Still, the danger and the high stakes associated with the war were impossible to ignore. “I remember a classmate coming into English class weeping,” says Spencer. Her young cousin had been one of the 262 people killed when the SS City of Benares, a passenger ship transporting child evacuees from war-torn Britain to Canada, was sunk by a German U-boat in September 1940.

As Spencer and his peers progressed in their studies, their attention was increasingly focused on the combat taking place overseas. “We knew there was a war on, that it created a cloud of uncertainty over our heads, and that we were going to have a part in it one way or the other,” says Spencer.

He joined McGill’s Canadian Officer Training Corps, which offered students military instruction. Among other things, “we were taught to strip and reassemble a light machine gun and to use a gas mask and an anti-gas cape.”

After graduating, he briefly worked as an elementary school teacher, then joined the Canadian Forces, serving in Britain and Northwest Europe between 1942 and 1946. He had a couple of close calls. At one point, a tank driver standing next to Spencer was killed. On another occasion, shrapnel sliced through Spencer’s leather jacket and uniform and cut his binoculars in two.

In a 2020 interview with the Ottawa Citizen, Spencer described what it felt like to serve in the war.

“We were in danger all the time and well aware of it. Was I frightened? Of course I was frightened, but I just carried on. We knew it had to be done.”

At the end of the war, Spencer stayed in Europe for several months, first to work on a history of his regiment, then to contribute to another project about the battle for Normandy. Along the way, he met a librarian who would return with him to Canada as his wife.

Spencer earned a master’s degree from the University of Toronto, a doctorate from Oxford, and then returned to U of T to begin a 36-year career in the Department of History. He became the associate dean of the School of Graduate Studies and the founding director of U of T’s Centre for International Studies.

Remember that small loan he received as an undergraduate? McGill didn’t forget it.

In 1945, while Spencer was still serving in Europe and on the march with his regiment, “I received a letter from McGill’s chief accountant, reminding me of an unpaid loan balance. Three months later, he wrote again, thanking me ‘for the conscientious manner in which this obligation has been discharged.’”

A three-time graduate

“The country was at war,” says Benjamin Gersovitz, BSc’40, BEng’44, MEng’48, describing the day-to-day environment of McGill during the late 1930s and early ‘40s. “Most people, I think, were very serious in the sense that frivolous parties and so on were not [popular], and the campus was rather subdued,” says the 102-year-old. Students were expected to focus on their studies and to make the most of their opportunities at McGill. After all, others weren’t so lucky.

Gersovitz didn’t qualify for military duty – his eyesight was regarded as a problem – but some of his friends would see action during the Second World War. They didn’t all come back.

He earned his first degree at McGill in science in 1940, hoping to go on to medical school. He applied to McGill, but wasn’t accepted. He understood that marks weren’t the only factor.

have both taught at McGill.

Credit: Owen Egan and Joni Dufour

Like many other universities at the time, including Harvard, Columbia, and Yale, McGill had taken measures to restrict the number of Jewish students it accepted. It was particularly difficult for a Jewish student to earn admission to McGill’s Faculty of Medicine.

“It was a disappointment,” says Gersovitz. “Many of the courses that I had taken in science” were selected with an eye towards preparing him for future medical studies.

Gersovitz says the Jewish community in Montreal was quite aware of what was going on. “People felt this was very discriminatory.”

It didn’t take him long to pivot towards a new path, though. He applied to McGill once again, this time for an undergraduate degree in civil engineering. He would go on to complete a master’s degree in the same discipline at McGill in 1948.

As I chat with Gersovitz at his kitchen table in Westmount, his daughter Julia Gersovitz, BSc(Arch)’75, BArch’75, a professor of practice at McGill’s Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture, sits with us. She shows me an elegantly crafted bracelet that her father designed and created for her.

“My father can really do almost anything with his hands,” she says. “He received his carpenter’s license when he was very young. He can build anything. Bring him any material—wood, concrete, metal, silver—this is the man for you. If you are ever [trapped] on a desert island, get my dad.”

He was four years older than most of his classmates in engineering – unlike them, he had already completed one university degree. Despite the age difference, some of his oldest and closest friendships began in his engineering courses. The class sizes were considerably smaller than they had been in science, so students had the chance to get to know each other better.

Gersovitz became the president of one of McGill’s most fabled student clubs, the McGill Debating Union. He enjoyed watching the debates, but didn’t take part in the action. “It was really a question of organizing [the club’s activities], not really a matter of participating, but organizing and making sure that the whole thing ran smoothly,” he says.

His first full-time job after leaving McGill was at Trust Fund Steel. The office was on the corner of Sainte-Catherine and Peel. When Germany officially surrendered in May 1945, he remembers looking out the office window and watching as hundreds of jubilant Montrealers poured out into the streets to celebrate. “There was so much joy.”

Gersovitz returned to the Faculty of Engineering in the early 1960s, teaching there for a decade. At one point, he constructed a five-foot long slide rule as a prop to instruct students on the proper way to use the tool. Students returned the favour, building him a gigantic tie that paid homage to the stylish wool ties he frequently wore (handwoven by an Austrian baroness who lived downtown).

He spent most of his career at SNC Lavalin, finally retiring at the age of 81.

While McGill might have been a more restrained place during the war years, there were still moments of fun. Gersovitz did attend one very fateful dance at Macdonald College, a formal affair that required a white tie.

“The young [woman] who invited me was not the person I ended up with!” he recalls, with a laugh. He sat at a table and took notice of another female student. She noticed him too. “She started throwing jellybeans at me!” Sarah Gammer was studying to be a teacher. She would go on to become a prominent Montreal artist. They got married in 1944 and remained together until her death in 2007.

“I have my mother’s dance card” from that night, says Julia Gersovitz. “[She] kept it as a precious remembrance of that time. You can see my dad’s name starts to appear on it more and more often as the night went on.”