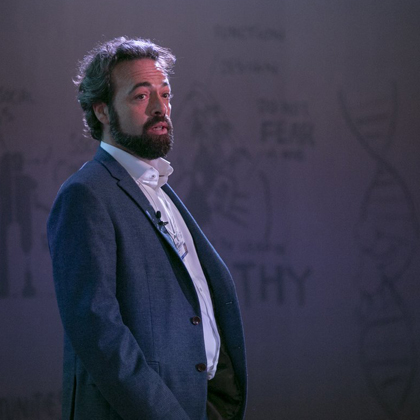

Etienne de Villers-Sidani, MDCM’00, has developed an eye-tracking software technology that would enable patients who can’t talk because of paralysis, or intubation in intensive care, to communicate using simple eye movements.

“Communication is so important to quality of care and quality of life for these patients, and it’s very frustrating when they can’t communicate what they need and want. Patients may want to talk about their discomfort, pain or positioning, or talk to loved ones about their feelings,” says de Villers-Sidani, an associate professor of neurology and neurosurgery at the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital.

His company, Innodem Neurosciences, is now pilot-testing a novel app, called Pigio™, that works with any smart phone or tablet equipped with a camera to track and analyze the gaze patterns of patients, who suffer from neurological conditions such as stroke or Amytrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) and can no longer communicate. Patients can control a cursor on their devices using only their eye movements and this allows them to communicate rapidly with healthcare staff or family members by selecting pre-defined sentences or words on the screen.

As a neurologist who regularly sees patients at the Neuro’s ALS clinic, de Villers-Sidani saw an urgent need for a fast, user-friendly device that would allow patients to communicate much more effectively than with the printed letter boards currently used, which are slow, limited and impractical for patients and healthcare professionals. The Pigio™ software will also be cheaper than the sophisticated eye-tracking systems (using infra-red cameras) on the market. “Most patients and clinics can’t afford and don’t have access to devices that cost $8,000,” he says.

De Villers-Sidani is aiming for his more intuitive and affordable mobile communication device to become the global standard of care. “We’ll create different modules for different types of patients and healthcare professionals, such as neurologists, nurses and speech therapists. It will be easy to create updates based on patterns of usage and requests, so we can make this very personalized with entertainment options as well,” he says.

Innodem received backing from CENTECH, a Montreal-based technology incubator, earlier this year. “We want to make this technology available to the public and healthcare professionals in January 2019. The next round of financing from investors will help us to commercialize and release it in North America, and then we’ll build the app for Europe and Asia.”

De Villers-Sidani chose the name Innodem to suggest innovation and democratization. “The core value of our company is to make new technologies and innovations accessible to all patients,” he says, noting that Pigio™ evokes the carrier pigeon and “we wanted to express that this mobile communication device will make people freer and more autonomous.”