Thomas Neill Cream, MDCM 1876, enrolled in McGill’s medical school in 1872 as the scion of a prosperous family and as a well-respected member of Quebec City’s anglophone community. He was a hard worker, a Sunday school teacher, a member of his church choir with a notably fine voice. His neighbours joined with his boarding-school teachers in the opinion that he was an altogether fine young man of excellent character.

He left McGill a spendthrift, vain and unpleasant in manner, avoided by his peers and arousing the distaste of his professors. One of his former instructors at McGill remembered Cream as being “rather wild and fond of ostentatious display of clothing and jewelry.”

His newly acquired knowledge of medicine, along with his status as a member of one of society’s most respected professions, empowered Cream to make his mark on history as one of the most notorious serial killers of the Victorian Age.

“What he seems to have gleaned from his medical training is that he has this God-like ability to preserve life, or take it. And he does,” explains Dean Jobb, author of The Case of the Murderous Doctor Cream (Harper Collins, 2021).

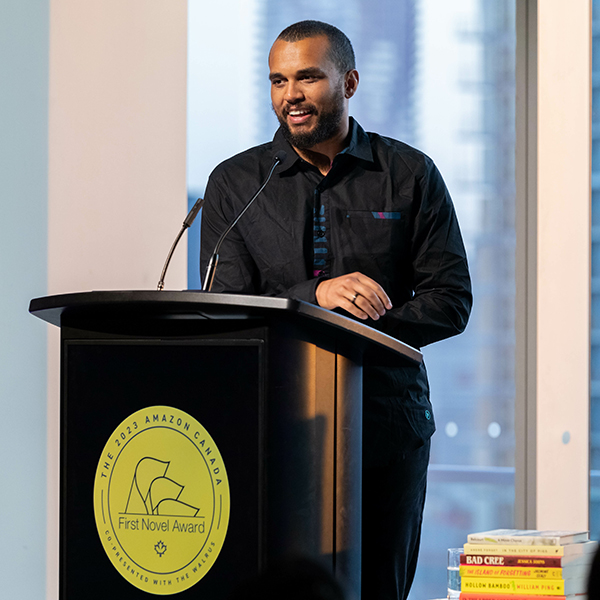

Jobb’s monthly column on true crime, “Stranger Than Fiction,” appears in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, and his last book, about a charismatic con man in Chicago at the dawn of the Roaring Twenties, won the Arthur Ellis Award from the Crime Writers of Canada. In his new book, he turns his attention to the McGill medical graduate who became notorious as The Lambeth Poisoner.

Delving into primary sources and contemporary accounts from Ontario, Quebec, Illinois and Great Britain – some of which had not been reviewed in over a century – Jobb explores the life of a cold-blooded killer who refined his methods and escalated his crimes until the final murder spree that led to his capture by London’s Scotland Yard.

Of Cream’s known and likely victims, most were female servants or prostitutes – “lower-class” women with precarious lives. As a specialist in midwifery, Cream’s medical practice specialized in abortions, which brought the desperate to his door.

“I think it’s important when you’re reconstructing the past, to try to understand what greater forces were at play. I wanted to understand the status of women in Victorian society, and how that played into driving victims into his clutches,” says Jobb.

Cream’s first likely crime came shortly after his graduation from McGill in 1876, when a fire broke out in the room that he had been renting, while he was ostensibly out of town. Firefighters suspected arson, and Cream’s insurers refused to pay his excessive claim. The presence of a skeleton in the room was explained by Cream’s medical studies. Its presence in his bed, while pointing to a possible attempt to fake his death, was not explained at all.

This seeming willingness to not dig beneath Cream’s respectable surface paid off for him again and again. Flora Brooks, his wife, died after taking pills mailed to her by her absent husband. Catharine Gardner, a patient in London, Ontario, was murdered within steps of his practice by chloroform (the subject of his medical school thesis). Deaths of young women in Chicago were blamed on a midwife and a pharmacist’s error.

Only when he poisoned a respectable man, Daniel Stott of Grand Prairie, Illinois (some suspected that Stott’s wife might have been Cream’s accomplice) was Cream finally convicted and sent to jail. Even then, he was able to use his family’s wealth and connections to lobby for a pardon. He served only 10 years.

Mere months after being released from prison in Illinois in 1891, Cream moved to London, England, where he had studied at Saint Thomas’s hospital after fleeing marital life.

Like Jack the Ripper three years earlier, Cream turned his murderous attentions to prostitutes and, as in Chicago and Canada, his social status and that of his victims helped prolong his killing spree: his first victim, Ellen Donworth, was assumed to have committed suicide. No questions were asked as to how she might have acquired the strychnine that killed her, despite it being a controlled substance.

His next, Matilda Clover, was assumed after a cursory examination to have died from heart failure resulting from delirium tremens. Information from a friend and fellow prostitute that the victim had claimed to have been given poison was ignored.

Jobb believes that Cream could have continued poisoning his way through the English-speaking world unstopped, were it not for the letters he wrote that ultimately incriminated him and led to his conviction.

Those letters, sent to a number of prominent Londoners (a socialite, a Member of Parliament, a physician to the Royal Family among them) under an alias, threatened to accuse them of murdering Cream’s victims unless they paid up. Most of the blackmail targets turned the letters over to Scotland Yard.

The police, by and large, ignored them – not even bothering to find out if the women named in them as victims even existed. It wasn’t until the deaths of Alice Marsh and Emma Shrivell (Cream’s first apparent double murder) that the investigation started in earnest and – eventually – the police put together a fuller picture of the scale of Cream’s crimes, linking him to the deaths through his handwriting.

There’s no evidence Cream ever tried to follow through on his blackmail attempts, however, and a similar letter was precisely how he had eventually been convicted for the murder of Stott in Illinois. Jobb believes that Cream wanted acknowledgement for what he saw as his achievements.

“These letters were a way for him to claim credit. Somewhere in his psyche, he wanted people to know what an efficient and ruthless killer he was.”

Ultimately, Cream was convicted and hanged for his crimes. For a long time, he was considered to have been one of the most notorious serial killers of the Victorian age, his waxen likeness worthy of a home in Madame Tussauds’ Chamber of Horrors.

Jobb feels that Cream’s story has resonance, even still. Serial killers are difficult to identify even today.

He points to the case of Bruce McArthur in Toronto, who preyed on particularly vulnerable members of that city’s gay community for years before being caught. Members of the gay community had tried to get the police to consider the possibility of a serial killer, but were initially brushed aside.

“It’s an echo to today’s time. It’s still hard to detect serial killers, because investigators need to find links between cases that happen in different places, and in somewhat different ways,” says Jobb, “And often the victims are vulnerable people… that are not necessarily going to seek police protection.”