Nearly half a century ago, Balfour Mount put his stamp on contemporary medicine by launching and rigorously testing a radical new idea: whole-person care for a human being who is dying.

The young surgical oncologist called it “palliative” care. “The etymology of the word was perfect,” Mount told one interviewer. “It means ‘to improve the quality of.’” Mount developed the world’s first comprehensive palliative care service based in a teaching hospital as an audacious pilot project at the Royal Victoria Hospital in 1975.

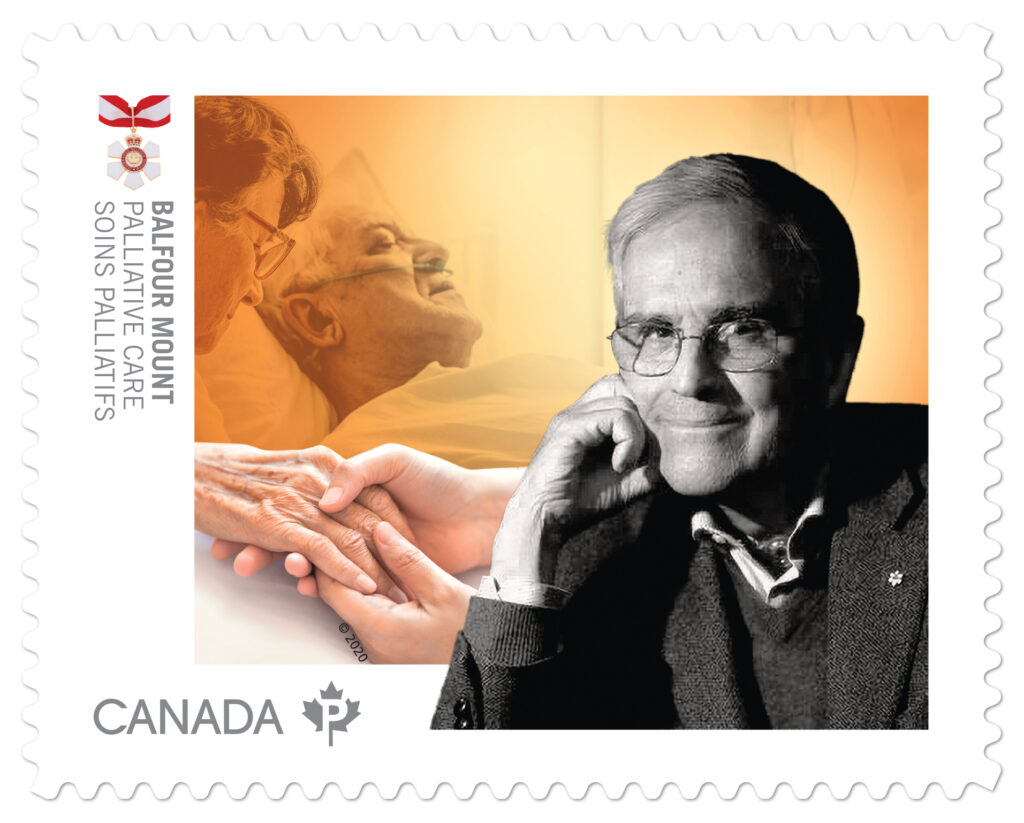

In September, Canada Post issued a commemorative stamp saluting Mount as a medical groundbreaker for his transformative work in the field of palliative care. In addition to Mount, the special edition set celebrates the work of five other trailblazing physicians and medical researchers.

It has been an eventful autumn for the palliative care pioneer. Mount’s memoir, Ten Thousand Crossroads: The Path As I Remember It, published by McGill-Queen’s Press, came out last month.

Mount was inspired and driven to investigate and implement a new approach for taking care of the dying after hearing Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, the Swiss-born author of the 1969 book On Death and Dying, give a lecture to a packed auditorium at McGill’s Faculty of Medicine.

“Kübler-Ross was an absolutely galvanizing speaker. She drew welcome attention to the fact that in Western culture we deny death and are very uncomfortable with the topic, and we don’t treat the dying person with openness. That made a big impression on me working as a cancer surgeon at the Royal Vic,” recalls Mount, who completed his residency training in urology at McGill in 1968, and surgical oncology training at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York in 1970.

Mount promptly did a study to investigate the attitudes towards death and dying among medical and paramedical staff and critically ill patients at his own hospital. His findings were clear, devastating and a call to action:

“The data emphasize the patient’s desire for complete openness and honesty in discussions regarding diagnosis and prognosis, the physician’s reluctance to be that candid, the [medical] resident’s relative lack of concern for the patient’s emotional needs, and the social worker’s tendency to minimize the problem. There was a tendency to see our colleagues’ shortcomings more easily than our own,” he reported in the journal Urology.

To see firsthand how to improve care for the dying, Mount visited a hospice described in the Kübler-Ross book, St. Christopher’s Hospice in London, Britain. He learned from its founder Dame Cecily Saunders, DSc’13, and the hospice staff how total pain control and optimal quality of life could be achieved by meeting the needs of patients and their families in all dimensions: medical, social, psychological, and spiritual.

“The visit was an eye opener,” Mount says. “The attention to detail and extraordinary level of care were almost beyond words.”

As a doctor and researcher, Mount believed the approach modelled at St. Christopher’s had to be scientifically evaluated and, if proven effective, integrated into mainstream medicine and hospitals across North America. For the greatest social impact and to be affordable, palliative care needed to be offered and available to the 70 per cent of Canadians who were dying in institutions and not just in hospices.

Armed with evidence that end-of-life care was poor at the Royal Vic, a leading teaching hospital proud of its accomplishments, Mount presented his case to the hospital and offered a promising practical solution. He received the Royal Vic board’s approval for a two-year pilot study, and launched a comprehensive palliative care project at a time when budgets were tight.

The pilot included a 12-bed palliative care unit staffed by a multidisciplinary team, a consultation program for acute care wards, a home care service, a bereavement follow-up program, teaching, and a research arm to evaluate its impact on patients and their families. (It has now expanded into Palliative Care McGill and the Balfour Mount Palliative Care Unit at the Glen site of the McGill University Health Centre.)

“As a medical scientist doing studies on the treatment of urological cancer, I thought you can’t ask an important research question and not answer it. It seemed very natural to me that you couldn’t mess around by doing a study of this new approach to care for the dying lightly,” says Mount, who credits his Royal Vic collaborators Ina Cummings, MDCM’64, and John Scott for the high quality of the pioneering program.

Following the resounding success of the pilot study, published in the Journal of Urology in 1976, Mount became a torch-bearer for the cause of palliative care, disseminating the findings from the Royal Vic’s palliative care experiment through visiting lectures across Canada and the United States, Europe, Israel, Australia, Japan and China.

In his memoir Ten Thousand Crossroads, Mount covers much of this ground, exploring the important role that McGill and the Royal Vic played in the development of palliative care (with the invaluable support of allies like the late Kappy Flanders, who became both an instrumental champion for the cause and a close friend). The book also recounts Mount’s interactions with the Dalai Lama and Mother Thersa and the circumstances that led to Pope John Paul II praying for Mount’s wellbeing during a difficult surgery.

McGill’s International Congress on Palliative Care, launched by Mount in 1976 with Saunders and Kübler-Ross in attendance, has inspired palliative care practitioners from 50 to 60 countries, who have gathered in Montreal every two years for more than four decades.

“The congress brought together people from every corner of the world for five days, sharing different perspectives and approaches to care of the dying from many cultures. It includes a film festival and was hugely important for teaching, spreading the message and building a strong sense of international community in the field,” says Linda Guignion, BA’71, MEd’73, Mount’s wife and a teacher in the Montreal area for over 30 years.

Through decades of championing the palliative care movement, both locally and globally, Mount emphasized a core concept: the power of healing connections between the caregiver and patient in moving from suffering to a sense of well-being.

“A major goal of palliative care is pain and symptom control at a very exquisite level so the person can be met with a listening ear. It’s not about sedating people but controlling pain so the patient can be alert and able to relate to others,” he explains. “Our deeper understanding of the human psyche makes it clear that what we all seek are healing connections. What we’re trying to do in palliative care, and all medical care, is establish healing connections to be experienced by those who are ill or dying and their families.”

As the father of palliative care in North America, Mount’s passion for healing when there is no cure carries on through the generations of healthcare professionals he has influenced, and the many patients and families they have treated:

“Balfour Mount is a visionary and compassionate team leader, but most of all a teacher who has molded, inspired and stimulated thousands of young medical students, physicians and other healthcare professionals here at McGill and internationally,” says Bernard Lapointe, McGill’s Eric M. Flanders Chair in Palliative Medicine. “The fully integrated model of palliative care he developed in a McGill-affiliated hospital was a true innovation and that model is now replicated across the world.”