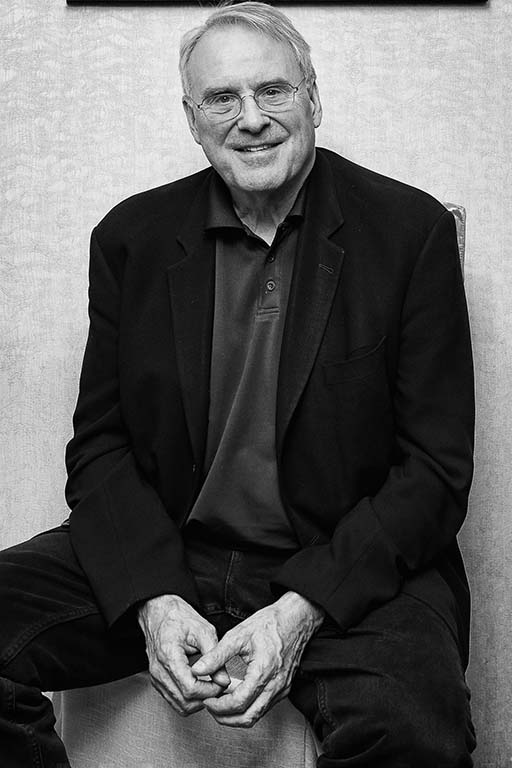

Ken Dryden, LLB’73, started sounding the alarm about the dangers of concussions several years ago with the growing conviction that it was the biggest issue facing sports.

The former Montreal Canadiens goalie, a six-time Stanley Cup winner and a member of the Hockey Hall of Fame, wrote pieces about his concerns for such publications as the Globe and Mail, La Presse and Grantland, but not much changed.

“Years were passing and seasons were being played. And I came to be reminded, again, that awareness is one thing, and actually seeing actions taken that are consistent with the dimensions of the problem, that’s quite another.”

By 2015, Dryden was quite certain he would write a book on the topic when he heard on the radio that former player Steve Montador had been found dead in his Mississauga home, nearly three years after playing his last NHL game with the Chicago Blackhawks.

Montador, a popular figure with former teammates, had struggled with addiction and the effects of concussions. He was only 35.

With Montador’s family on board, Dryden decided to write his latest book, Game Change, about the defenceman who had played for six teams in 12 NHL seasons. The opening narrative describes a neuropathologist’s examination of Montador’s brain that winds its way to the disturbing conclusion that he had chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative condition linked to repeated head trauma.

Dryden weaves into the book how hockey has evolved from 1875, when McGill students took part in a now famous game at Victoria Skating Rink in Montreal. Where NHL players once paced themselves through long shifts and stickhandled up the ice, they now pass in a full-sprint game with little time and space on the ice and more collisions.

The game has changed, and so should the rules, Dryden suggests, to reduce hits to the head.

“What I tried to do with the story of the game, is to say, you think that by saying that a game can’t change, you’re wrapping yourself in the flag of the purist and the traditionalist. Well, if you really knew the history of this game, you would see how this game has changed overwhelmingly in its time. And that I would bet that you, as the critic of any kind of comment or suggestion this way, will not know that for the first 54 years of hockey you couldn’t make a forward pass. That was the nature of the game.”

Dryden spoke with former NHLers Keith Primeau and Marc Savard about their struggles with concussions (both men dealt with severe and debilitating symptoms for years). He also talked to Toronto-based neurosurgeon Karen Johnston (the former director of the concussion program at the McGill Sport Medicine Clinic) and McGill neurology and neurosurgery professor Alain Ptito, BA’75, who have collaborated on concussion research and raised awareness about the injury.

Ultimately, the answer for brain injuries in professional sports rests with the decision-makers, says Dryden, who tries to prod NHL commissioner Gary Bettman and the league into taking action to reduce blows to the head and offers suggestions on how to find a way to do that.

“There should be no such thing as a ‘legal’ check to the head,” Dryden writes. He also notes the phrase “finishing your check” once didn’t exist in hockey and to do so is interference (which should result in a penalty).

Game Change recently made the longlist of nominees for the B.C. National Award for Canadian Non-Fiction. At times heart-wrenching, it recounts how Montador, who suffered his first concussion at the age of 12, struggled with the effects of concussions at the end of his NHL career and afterward, including memory problems and depression. He also battled addiction. A former teammate recounted how Montador would spend time at Starbucks on his laptop researching concussions and what was going to happen to him as a result.

How hard was it for Dryden to write the book?

“Most of the time it was not hard at all because it was talking to people for whom Steve was such a vivid guy,” says Dryden, recalling many laughs. “He was just a very funny guy.”

Reading some of Montador’s journals toward the end was difficult, though. His deteriorating condition was obvious. “It was the changes of the handwriting … it was the way in which things would come out, that it was more frenzied, it was more incomprehensible. Those parts were very hard to deal with.”

Asked if Bettman has dropped the ball on this issue, Dryden responds that pointing fingers merely results in fingers pointed in other directions. “It doesn’t serve the purpose of things being better. And that’s what this is about.”

The hopeful part, according to Dryden, is that there are answers. “Football is a far harder story. If I was [NFL commissioner] Roger Goodell, I know a bunch of things I could do, but I’m not sure that I know what I could do that would really significantly change things. In hockey, the answers are not that hard.”