Am I special, or am I completely ordinary? Am I a strange one-off, or a quintessential member of a universal family? Is my existence the result of a freak accident or a chemical imperative?

These questions might sound like the existential musings of a glum teen, but change “I” to “we,” and they address central scientific issues in the work of chemist and Nobel laureate Jack Szostak, BSc’72, DSc’11.

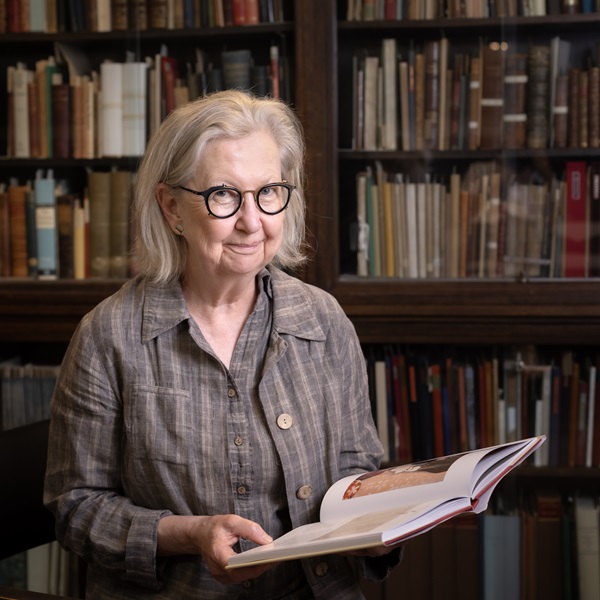

Szostak and his co-author, astrophysicist Mario Livio, chose a related question for the title of their recent book, Is Earth Exceptional? The Quest for Cosmic Life.

Flexing their complementary areas of expertise, Szostak and Livio report on emerging advances from the worlds of chemistry and astrophysics to explore two major, interrelated mysteries: How life emerged here on Earth, and whether we might find evidence of life on other planets or moons.

“At this point, we know that there are many, many places in our galaxy and in the universe that could support life. We don’t know if any of them actually do. We don’t know if we’re alone in the universe or life is everywhere,” says Szostak, the director of the University of Chicago’s Center for the Origins of Life. “It’s this big unanswered question.”

Szostak was a co-recipient of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his seminal work on the protective function of telomeres, which play a crucial role in safeguarding chromosomes. In his Nobel lecture after receiving the prize, Szostak said, “My first introduction to these issues came when I was an undergraduate student at McGill.”

“How did we get here? Are we alone in the universe? The fact that we can’t answer these questions right now is just a motivation for figuring out how to go about getting an answer.”

Jack Szostak, co-author of Is Earth Exceptional?

The first half of Is Earth Exceptional? focuses on our own planet’s wondrous transition from chemistry to biology billions of years ago.

Chemical reactions are universal. Every planet and moon features evidence of atoms and molecules combining and recombining to form all manners of materials. Earth, though, is the only place we know of (so far) where those reactions gave rise to DNA and RNA, and to cells and complex organisms capable of metabolizing, growing, reproducing, and interacting with their environment.

In the book, Szostak goes deep on what we know and don’t know about the emergence of life and attempts to resolve the freak accident/chemical imperative question.

“It relates to the work I do in my lab. Many of my colleagues are also trying to understand if there is a straightforward, plausible pathway to going from chemistry to biology,” he says of an area of research with philosophical as well as scientific implications. “I think almost everybody at some point wonders, ‘Why are we here?’ ‘How did we get here?’ Both personally and for life in general, I think it’s hard to not be curious about that.”

While many questions still remain, the emergence of life is growing less mysterious, and seemingly more probable in other places. Chemists and biologists have historically struggled with the question of how DNA’s self-replicating cycle could possibly have begun. DNA comes from other DNA, so how did it first emerge from the non-living chemistry that preceded it?

“DNA makes RNA, which makes proteins which do all the work [of replication]. Every part of that cycle requires every other part,” Szostak explains. “It’s very circular and self-referential. That made it very hard for people to think rationally about how life could have gotten started.”

In the book, he walks readers through some advanced science discoveries, including the major revelation that RNA can act as both genetic material and as a type of biological catalyst known as an enzyme. The molecule’s dual role helps explain how the DNA replication cycle could have first gotten rolling.

The second half of the book heads out into our solar system and well beyond in a search for signs of alien life. The authors speculate that some of the moons of Saturn and Jupiter, believed to have subsurface oceans, are potential candidates.

“We more or less divided up the main work, so that Mario talks about exoplanets and astronomy, and I talk more about the laboratory experiments, trying to understand how life could get started,” says Szostak.

“It was really fun because we could each read each other’s sections, make comments and try to ensure not just that everything was correct, but was explained in a really clear way that got the message across. It was a great experience.”

Here too, the questions span science and philosophy. Discovering life on even one other world would be both a major scientific advance and a huge disruption to our sense of Earth’s cosmic significance.

“If life is in two places, it means the path to getting there is just not that difficult,” Szostak says.

Even if the universe abounds in simple life forms, though, human-level complexity might still be a rarity.

“It could be the galaxy is teeming with planets basically covered in slime or bacteria. They might or might not have all the same underlying biochemistry. That would be scientifically interesting, but it would really leave open the question of the evolution of much more complex life forms.”

In fact, in Is Earth Exceptional, Szostak and Livio suggest that the journey from simple to complex organisms might be more difficult, mysterious, and improbable than the mere emergence of simple life. Furthermore, complex life itself is no guarantor of intelligent life.

“We only have one example: Humans. We can’t really say whether the evolution of intelligent life is an incredibly rare event,” he says.

Spoiler alert: Is Earth Exceptional? does not definitely answer its own question. Neither, though, do the authors accept that those answers will always be shrouded in mystery.

“These are such fundamental questions: How did we get here? Are we alone in the universe? The fact that we can’t answer these questions right now is just a motivation for figuring out how to go about getting an answer,” Szostak says.

“I don’t have a strong gut feeling about what the answer is. That’s one of the things that motivates me to be involved in this work. I hope, though, the answer is that life is not rare and that we’re not unique.”