For all the havoc it wreaks, lung cancer gets short shrift.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths world-wide, but it’s underfunded and understudied, according to the experts at McGill’s Rosalind and Morris Goodman Cancer Research Centre (GCRC).

Two factors contribute to the low investment: the stigma around lung cancer, and grim survival rates means few patients advocating for research.

But new efforts are afoot at McGill to tackle the disease as a cancer grand challenge, using a more collaborative team science approach to speed up research outcomes.

In June, the Goodman Cancer Research Gala raised more than $3 million, a record for the biennial fundraising event, and launched the Lung Cancer Network. The project aims to unite basic and clinician scientists and clinicians in Montreal – and across Canada and internationally – and double the number of lung cancer survivors in the next decade.

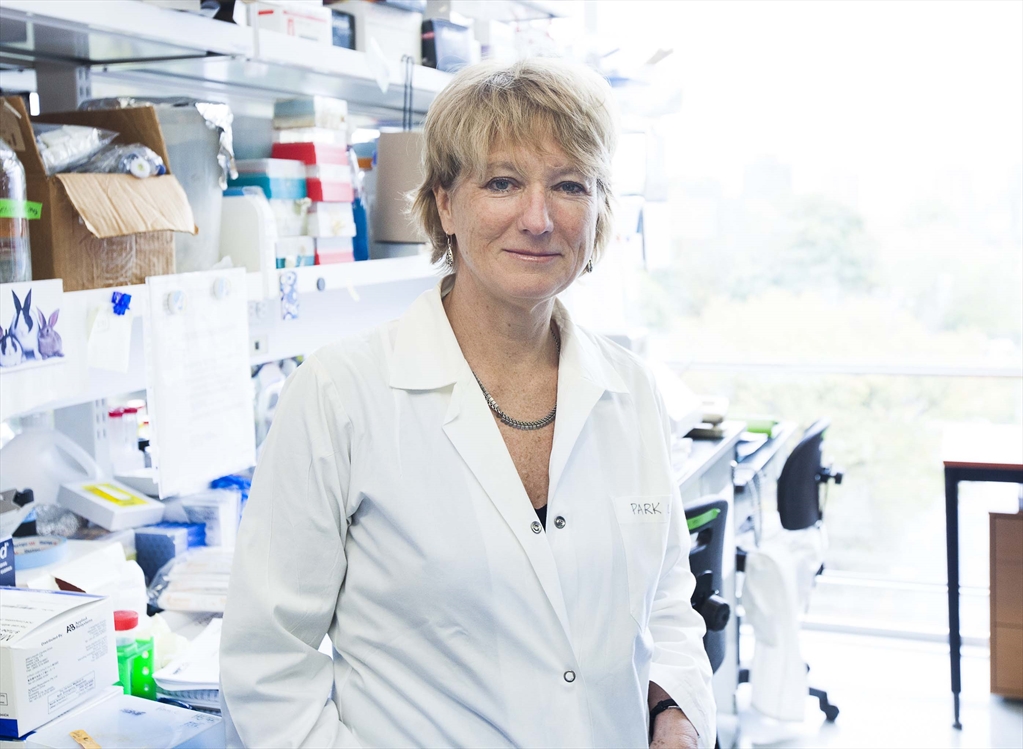

The network was the wish of Rosalind Goodman, BA’63, LLD’11, a tireless champion of the centre, who died of lung cancer as a non-smoker, says Dr. Morag Park, the GCRC’s director.

Credit: Claudio Calligaris

“The big challenge with lung cancer is that it’s a deadly disease,” says Park, a professor of biochemistry. “It has a stigma because it’s associated with smoking. But as many non-smokers die of lung cancer as women die of breast cancer every year in Canada.”

Although the GCRC launched the project, the collaborative network will be an entity unto itself. “We’re joining this fight. I think the most important thing is that everybody is joining together,” Park says.

“Multiple centres in hospital institutions will start working together towards this common goal. It’s to eliminate duplication, to open the same trials, to share data.”

People always collaborate, Park says, “the difference here is that it is a plan, it’s a strategy with a common goal. It’s a strategy to understand why some patients respond to therapy and others don’t.”

In Montreal, which has many lung cancer patients and very high clinical volumes, the project aims to have both McGill-affiliated institutions and centres outside of the McGill network involved.

Why launch the network here?

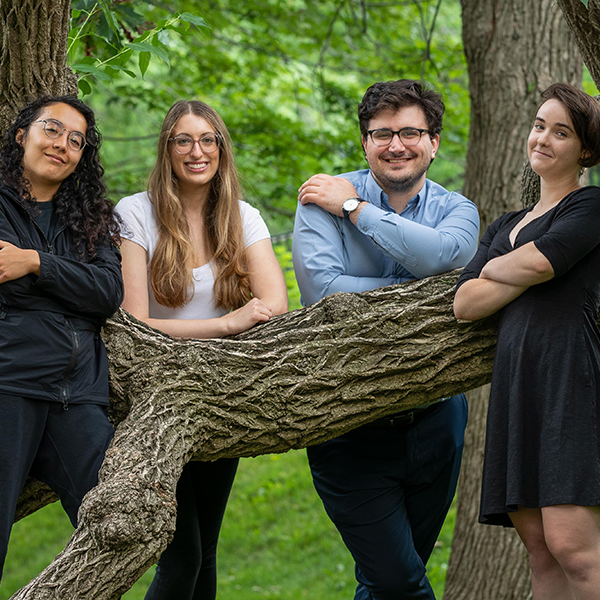

The city has centres for excellence, the patient population, and world-class physicians and scientists, says Dr. Logan Walsh, a GCRC scientist and the inaugural chair holder of the new Rosalind Goodman Chair in Lung Cancer Research.

“And that’s the one thing we have that other centres don’t have … this combination, and the patient population because that’s the most important thing.” An assistant professor of human genetics, Walsh believes the network will be able to provide patients with the top therapeutic options, and also develop the best choices for future patients. “I think it’s as simple as that.”

Walsh, who was recruited from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, mentions several broad goals from his perspective. One is an initiative aimed at moving away from delivering treatments based on rudimentary data with little knowledge of whether they’ll work. The goal, he says, is to use the most promising scientific techniques to provide a predictive analysis so that patients are assigned treatments with the highest probability of efficacy.

Unfortunately, a lot of patients will get chemotherapy that’s harmful to them without seeing any response and they will have never seen any response, Walsh explains. “So, I think one of the things that’s really important is, even with our current therapeutic regimens, that we start to really do the biology and the bio-marker discovery and understand who will or will not likely respond, so that we can start to really triage patients in a much more educated format.”

Another initiative, which just started, involves developing a personalized medicine pipeline for patients whose lung cancer they know will recur. “We’re developing this therapeutic pipeline for the patients by bringing some of their tumors into the lab, figuring out and testing which drugs are most likely to work against their individual tumors, and then coming back to them after they recur,” Walsh says. He describes this approach as “the very essence of personalized medicine – one that gives peace of mind to the lung cancer survivor.”

Dr. Jonathan Spicer, BSc’01, MDCM’05, PhD’14, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC), who has been involved in launching the network, believes it will make Montreal more attractive to pharmaceutical companies for clinical trials. These trials could provide new therapies to patients directly as world-firsts, “so giving Quebec patients access to the latest and the newest and the best, and also be able to derive a lot of science from it, adds Spicer, an assistant professor in the Division of Thoracic Surgery.

in the new Lung Cancer Network

Credit: Owen Egan

In some sense, Spicer says, the science is increasingly coming directly from the patients themselves. “Unless you have these cutting-edge newest clinical trials in place … and the pipeline to be able to process and analyze the tissues and bloods that are generated from these patients being treated, then you’re not really in a position to be at the leading edge of the research and the new discoveries that are going to come.”

A Phase 3 clinical trial for immunotherapy for lung cancer is underway at about 140 sites around the world, including the MUHC, which enrolled the first patient and has the most to date, says Spicer.

They’ve expanded the trial so that it’s available at the CHUM, in St-Jérôme, Trois-Rivières, and Western Quebec, Spicer says.

In fact, he expects that when the international trial ends in 2021 and the results are published, that the Quebec contribution to the study, including more than 600 patients, will be the most significant.

“The reason we’re using this as an exemplar is because this demonstrates to pharma our ability to be a high-level cancer centre as a network,” says Spicer.