Poke your head into a McGill research lab – particularly in the summer – and you might walk away thinking that some of those graduate students look awfully young. There is a reason for that. They probably aren’t graduate students.

In recent years, undergraduates at McGill have had access to a growing number of opportunities to dive into serious research work. Those opportunities will continue to expand, says Interim Deputy Provost (Student Life & Learning) Fabrice Labeau.

“We pride ourselves on being a research-intensive and student-centred university, in which teaching and learning is informed by the latest research,” says Labeau. “One of the key choices that McGill has made is to focus on having our professors, who are star researchers, [teach] in the classroom.”

Undergraduates with an interest in experiencing research for themselves should have the opportunity to flourish in such an environment, reasons Labeau. McGill has an array of programs designed to promote undergraduate research and these programs “allow students to apply their knowledge to real, current and cutting-edge research questions and problems.”

Victor Chisholm, BA’97, the undergraduate research officer for the Faculty of Science, plays a major role in coordinating some of those programs. “McGill is a special kind of university, where [undergraduates] get to participate in real research,” he says. “Not just lab courses that teach existing techniques, not just washing test tubes – they play active roles in research that pushes forward the frontier of knowledge.”

Investigating the Three Bares

And, in at least one instance, that research has helped us gain a better understanding of something that many McGillians stroll past on a daily basis.

Tara Allen-Flanagan, an art history and English literature student, spent much of last summer delving into art archives to find out everything she could about an iconic piece of McGill’s downtown campus – The Three Bares fountain.

The naked marble men holding up an earthen bowl on the lower field have been a familiar part of the McGill landscape for generations of students, but information about the fountain’s origins is almost as scant as the figures’ clothing. The official name of the statue is The Friendship Fountain, and it was crafted by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, whose family fame and wealth often overshadowed her artistic talent.

Vanderbilt Whitney’s papers were recently digitized for the Smithsonian Institutes Archives of American Art, and an exhibition about her sculpture – the first since her death in 1942 – was mounted this past spring in West Palm Beach. So the timing was right.

By poking through unlabeled files and cross-referencing letters, Allen-Flanagan, supported by an Arts Undergraduate Research Internship Award (ARIA), pieced together a narrative. And by working out the timing of the sculpture’s creation, Allen-Flanagan was able to find preliminary sketches of the sculpture, “as if it just popped out of thin air!”

Allen-Flanagan discovered the sculpture was commissioned for the New Arlington Hotel in Washington D.C., which was never built. Auguste Rodin himself critiqued a sketch of the main male figure, and the sculpture was carved in 1913.

All of this was lost in time, however, and when the fountain was donated to McGill in 1931, Allen-Flanagan says, “the three figures were hailed as representing England, Canada, and the United States coming together to hold up a bowl for the fertile soul of the nation! And this was sculpted in 1913 to decorate a hotel, when she was studying Greek myth.”

Gwendolyn Owens, director of McGill’s Visual Arts Collection, supervised Allen-Flanagan’s efforts. “I expected Tara would find back-and-forth letters, but not all of this amazing material. It’s a very complicated story that Tara made much more complicated by all she was able to find and figure out about these early sketches.”

The realization that there’s still so much to uncover in the world of art history led Allen-Flanagan to apply to graduate school.

What happens if a student isn’t enthralled by a research project? Owens says that realization can provide valuable insights of its own. She recalls one student who decided that art conservation –spending weeks at a time focused on the preservation of the same object – wasn’t for her. She pursued a career in history instead.

The ARIA program is administered by the Faculty of Arts Internship Office. “Unlike in the sciences, where it is common practice for upper level students to work in their professors’ labs, the opportunity to work directly with a professor on their research is less common in many arts disciplines,” says Anne Turner, BA’81, manager of the Faculty of Arts Internship Office.

She credits former dean of arts Christopher Manfredi (now McGill’s provost) as the driving force behind the creation of ARIA in 2010. “[He] recognized this [gap] in opportunities for arts undergraduates, particularly those who were contemplating academia as a career.” The program is largely funded by donors and by participating professors’ research grants. The Arts Undergraduate Society of McGill University and the Dean of Arts Development Fund also provide support.

Students who take on a summer ARIA position benefit from the mentorship of a faculty member, while professors gain keen assistants who contribute to their research agendas.

ARIA is only one of several programs at McGill that offer undergraduates the chance to take on research responsibilities under the supervision of McGill professors during the summer months. The Faculty of Engineering’s Summer Undergraduate Research in Engineering (SURE) Program, the Faculty of Science’s Science Undergraduate Research Awards (SURA) and the Faculty of Medicine’s Global Health Scholars program all offer undergraduates the opportunity to put their textbooks aside for the summer and to see what research looks like close up.

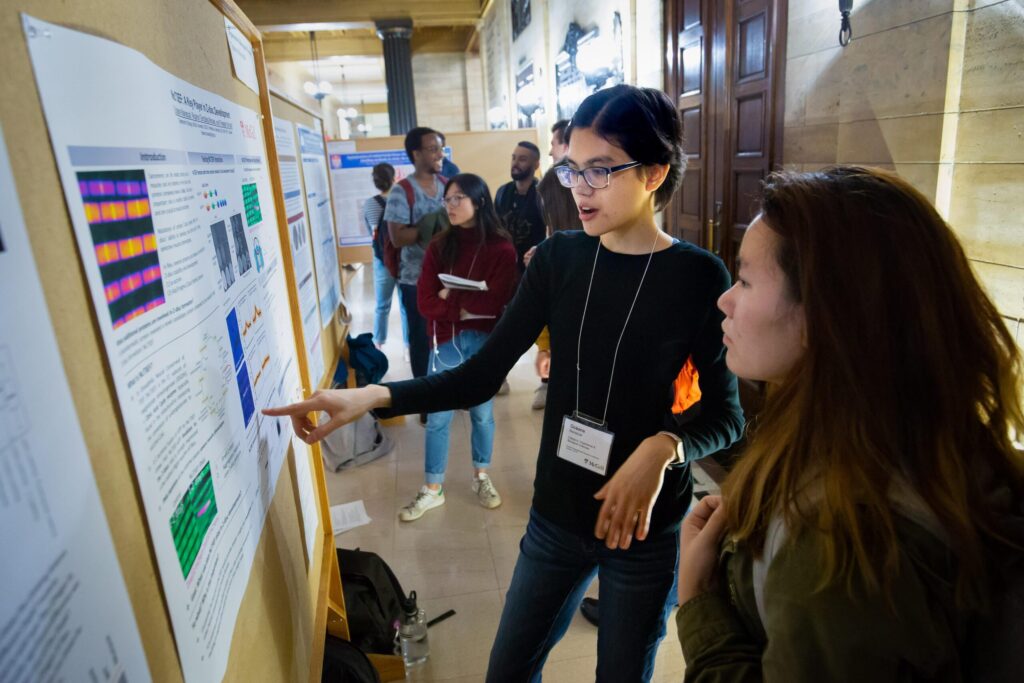

Like ARIA, these programs pay their undergraduate participants for their work. And, like ARIA, the programs all benefit from the support of generous donors. All four programs include major wrap-up events with research posters summarizing the projects that the students worked on.

Out in the field

Civil engineering student Amara Regehr took part in the SURE program last summer, working on a project that measured gas emissions from abandoned oil and gas wells in British Columbia. Her supervisor was assistant professor of civil engineering Mary Kang. Regehr worked closely with Kang on the planning for the project, on the data collection in the field, and on the data analysis.

Once in Fort St. John, B.C., (Regehr booked the flights and hotel, too), she and Kang drove around to examine sites. Because the wells were no longer in use, they should have been capped and buried quickly. But many were just abandoned and had been leaking gases like methane for years. “Companies don’t necessarily feel obliged to actually follow the protocol,” Regehr says.

She hopes to work with Kang in the future and she’s definitely thinking of focusing more on environmental issues in her final years at McGill. “SURE is really a great program,” says Regehr.

“Being able to learn outside the classroom is a wonderful thing,” says Chidinma Offoh-Robert, the director of administration for the Faculty of Engineering and the interim associate director of the McGill Engineering Student Centre.

Offoh-Robert says the SURE program often allows students to try their hand at something new. “You might see a student from mechanical engineering do a SURE [project] in electrical, or an architecture student who does one in civil. It allows our students to cross boundaries.”

Northern exposure

The McGill Global Health Scholars program also prides itself on its crossdisciplinary approach. While most of the students who take part in both its undergraduate and graduate streams hail from the Faculty of Medicine, students from other parts of the University are free to take part too. Steven Stechly would be one example.

Stechly, who is doing a double major in political science and psychology, worked on a project last summer addressing patterns of violence and intergenerational trauma. He took on the work in collaboration with the Cree Health Board in Waskaganish in the Eeyou Istchee territory that shares borders with northern Quebec. He was supervised by Anne Andermann, BSc’94, MDCM’02, an associate professor of family medicine.

Before heading north for his summer research project, Stechly did preparatory research in Montreal on “two-eyed seeing,” which is a way to incorporate Western approaches with Indigenous knowledge. He had many long phone conversations with those up north, including Cree elder George Diamond.

Much of his work focused on lateral violence, a term that originated on the West Coast that describes how the treatment by oppressors becomes so culturally entrenched that the behaviour is perpetuated within Indigenous communities – people treating others as they have historically been treated.

Elders in the community had proposed a shift in focus to kindness and the positive. Building on this idea and the work done before him – even researching the neurological effects of kindness – Stechly designed workshops on lateral kindness, another West Coast term that emphasizes resilience and social support.

To make these interactive workshops culturally relevant, Stechly used the Cree language as much as possible, and turned to the goose, which is central in Cree culture. Creating games that play on how geese work together and fly, for instance, “really engaged the youth,” he says. He adapted the workshop for different audiences. “Lateral kindness is going to be different in a health care setting, an educational setting, a youth protection services setting.

“It was an incredible experience,” says Stechly of last summer. He has applied to law school, and plans to focus on the challenges in administrative health, about which he learned so much.

Jill Baumgartner, an associate professor with the Institute for Health & Social Policy, has overseen the efforts of several undergraduates in the Global Health Scholars program and she is a firm believer in their ability to make significant contributions. “They’re dynamic, they’re smart. I schedule meetings with them on Fridays because I leave [work] feeling better about the world.”

Her projects, which employ both undergraduates and graduate students, explore the impact of air pollution on health, and are truly global in span from the Tibetan Plateau to Colombia. “It’s helpful to just have extra hands,” says Baumgartner. “We work [students] pretty hard, long days and there are lots of challenges from equipment breaking to bad weather.”

Baumgartner is often right there along with them, helping to troubleshoot and fix equipment, even scouring shops for a specific screw for an instrument. “It’s important for them to see these are not jobs we’re giving to them because they’re below us, these are jobs we do as well.”

Not all cut and dried

The Faculty of Science’s Victor Chisholm estimates that more than half of the undergraduates in his faculty take on at least one significant research project of some kind – some as part of an honours degree, some through the SURA program, and some through a series of independent research courses for undergraduates that are growing in popularity.

These classes, designated as ‘396’ courses in most departments, also frequently offer undergraduates a chance to explore unfamiliar terrain. “It allows students to do research outside their own home department,” says Chisholm.

“I think undergraduates recognize that research is an interesting thing to do, and they’re motivated [to do it],” says Earth and planetary sciences professor John Stix, the associate dean (research) in the Faculty of Science.

Stix, a volcanologist, frequently incorporates undergraduates as part of his research teams, taking them on expeditions as far afield as New Mexico and Iceland. “It’s not everybody’s cup of tea,” Stix says of research work. “[Some undergraduates] think there’s some sort of truth out there. Well, there may be some sort of truth out there, and research is trying to find the answer to something, but it’s not cut and dried.” Projects go awry, expected results go south, directions shift. Students learn that perseverance and an ability to adapt are key.

Biology student Océane Marescal found that out herself, working on a SURA project in the lab of associate professor of biology Frieder Schöck. “Research can be a lot of fun, but it’s also at times frustrating.”

Marescal spent the summer focusing on fruit flies – specifically a certain protein related to muscle fibers. She gained an appreciation for how fruit flies can serve as useful analogs for people in some ways – the work in Schöck’s lab could have implications for muscle diseases that afflict humans.

She is grateful for the chance to have contributed to such work and she is now applying for graduate studies “because of the amazing time I had in Dr. Schöck’s lab.”

David St-Amand, BSc’17, now pursuing a master’s degree in neuroscience, says his SURA experience helped prepare him for graduate studies. He gained confidence in his own skills and developed a better understanding of the interpersonal dynamics involved in working on a research team.

“I learned how important it is for [team members] to listen and communicate with each other in order to improve the experiment and do better research.”

There are other opportunities for students to take part in research at McGill. The Faculty of Law supports research assistantships and travel grants for research projects. Students in engineering and science-oriented faculties can apply for NSERC Undergraduate Research Awards (co-funded by participating professors and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council). McGill’s Social Equity and Diversity Education Office also supports undergraduates in summer research initiatives in collaboration with the ARIA and SURA programs.

Fabrice Labeau can list several ways in which these programs benefit undergraduates: “An understanding of the complexities and realities of research at the cutting edge; skills in terms of work prioritization, management and teamwork that will be applicable in any future career; an inspiration to maybe pursue a career in research.”

Looking back at her SURE experience, Amara Regehr says the chance to get involved in research was eye-opening.

“You see the university as not just your classes, but as the research university that it is.”

Maeve Haldane is a Montreal-based writer and a former editor of the McGill Reporter. Her work has recently appeared in Concordia University Magazine and The Montreal Gazette.