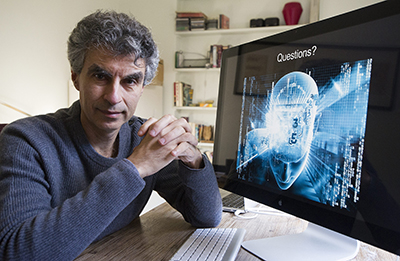

The announcements kept coming all through the fall. Key members of McGill’s Reasoning and Learning Lab, which has built up an international reputation for its contributions to machine learning, were taking on important roles for big-name companies in the burgeoning area of artificial intelligence (AI).

The first announcement, in September, involved Joëlle Pineau. With Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, BA’94, in attendance, Pineau was named the head of Facebook’s first-ever AI research lab in Canada. It’s a part-time position, one that will allow Pineau to remain at McGill as an associate professor of computer science and a co-director of the RL Lab.

Next up, in October, was Doina Precup. Also a co-director of the RL Lab, Precup was named as the head of another brand new AI research lab in Montreal, this time for the Google-owned DeepMind. Like Pineau’s, the position is part-time – enabling Precup to continue as an associate professor of computer science at McGill.

In November, yet another announcement involving yet another co-director of the RL Lab. Assistant professor of computer science Jackie Chi Kit Cheung will serve as the academic adviser for – you guessed it – a new AI research lab in Montreal. The Borealis AI lab is being created by the Royal Bank of Canada.

Samsung, Microsoft and the Thales Group (a Paris-based industrial giant specializing in aerospace and defense) all recently chose Montreal for their own new AI labs – all of them affiliated in some way with Yoshua Bengio, BEng’86, MSc’88, PhD’91, a professor of computer science and operations research at the Université de Montréal.

All that interest hasn’t escaped the notice of the Quebec government, which pledged $100 million towards further developing the province’s emergence as an AI powerhouse. Some of that money will go towards attracting and retaining talented AI specialists. Some will go towards the support of home-grown AI startups. The government also created an advisory committee to develop a strategic plan for spending that money effectively.

Martha Crago, BA’68, MSc(A)’70, PhD’88, McGill’s vice principal (research and innovation), sits on that committee (Bengio and Precup are both involved as official observers). “The government clearly recognizes that there is something special happening here,” says Crago.

The federal government has also been playing an important role. In 2016, the government’s Canada First Research Excellence Fund granted a combined $213 million to major initiatives at Montreal universities, including McGill’s Healthy Brains Healthy Lives (HBHL) project, that were all related to AI and machine learning. In the case of HBHL, Precup is serving as the project’s associate scientific director and HBHL will be using machine learning techniques to tackle mysteries related to mental illnesses and neurological disorders.

Montreal in the spotlight

At the press conference for the launch of Facebook’s AI lab in Montreal, Yann LeCun, the company’s director of artificial intelligence, made it plain that it’s no accident that the company decided to plant roots in Montreal. “Facebook chooses locations because of talent. We are attracted by talent.”

In a recent interview with The Canadian Press about the new Borealis AI lab, RBC chief science officer Foteini Agrafioti made the same point. “[Montreal] is absolutely one of the hottest places [for AI] not only in Canada but on Earth right now.”

A lot of that has to do with McGill’s RL Lab, where Pineau and Precup in particular have emerged as leading experts in a branch of AI known as reinforcement learning.

“It’s been a whirlwind,” says Precup of all the recent attention that has been focused on Montreal’s thriving AI sector. “The last year has been pretty miraculous as far as I’m concerned. And it’s interesting because people often say, ‘Oh, there is all this new stuff in [AI].’ From my point of view, the type of research that I’m doing hasn’t really changed all that much in the last five years. But now people realize that these methods actually work.”

So what did change? In short, the technology caught up with the theory. The most promising new AI techniques require huge amounts of data and a computing infrastructure that’s powerful enough to pore through all that data quickly and draw conclusions from it.

And thanks to these advances in technology, a bold new era of AI is upon us. “We’ve seen an incredible improvement in the performance of image recognition systems, video analysis systems, speech recognition systems, text translation – all of those systems use deep learning,” said Lecun in October when he was the featured attraction at a McGill event organized by the University’s Marcel Desautels Institute for Integrated Management.

“The most exciting areas”

Both deep learning and reinforcement learning are geared towards building machine systems that are capable of developing a certain degree of autonomy in how they go about executing their tasks and making determinations about the data they deal with. “These two subfields [of AI] are probably the most exciting areas to be working in right now,” says Pineau.

Pineau describes deep learning as “a show-and-tell approach to AI.” Instead of constantly issuing and refining instructions to a machine system, the idea is to “show the machine how something is done. With deep learning, I can show the machine images of cats and dogs, I can tell the machine what is on these images and how to tell the differences between a cat and a dog. Then, by presenting it with thousands or even millions of images of cats and dogs, it will learn to recognize patterns on its own and it will make accurate assessments.”

Bengio is internationally recognized as a seminal figure in deep learning. Wired magazine referred to him as “one of the original musketeers of deep learning” along with LeCun and the University of Toronto’s Geoffrey Hinton (the three frequent collaborators had their own nickname for themselves – “the deep learning conspiracy”).

Deep learning relies on multiple layers of processing and an artificial neural network that roughly mimics the functioning of the human brain’s enormous network of neurons.

Reinforcement learning operates a little differently. “It is about training a system for, essentially, good behaviour,” explains Pineau. Carefully crafted algorithms compel a machine system to pursue certain “rewards” and the system evolves and adapts in pursuit of those rewards. “If we’re building a computer system to play chess or to play a game of Go, the reward is to win the game,” explains Pineau. “After a while, the system will notice that a certain sequence of actions is more likely to lead to winning the game.”

Reinforcement learning techniques played a vital role, for instance, in AlphaGo’s stunning win in 2016 over leading human Go player Lee Sedol – a victory for machine over man that has been widely compared to the triumph of IBM’s Watson supercomputer on Jeopardy! Two members of DeepMind’s AlphaGo team were McGill computer science graduates – Marc Lanctot, BSc’03, MSc’05, and Arthur Guez, BSc’09, MSc’10.

“Reinforcement learning is about [the machine] learning from interaction, rather than always being told what to do,” says Precup. “So you have programs that train by being put in an environment, then interacting with it and exploring different possible actions. [The program] will make some mistakes along the way, but it will learn from those mistakes.”

The two approaches are often complementary. “I will use deep learning to understand complex information and I will use reinforcement learning to adapt the behaviour [of a machine system],” says Pineau. Combining the two, says Precup, has “already led to a lot of interesting things in the areas of robotics and automotive control. It applies to finance, it applies to medicine – things like patient monitoring. It applies to drug treatment design. It applies to the control of power plants.”

One of the reasons why Montreal is attracting so much attention in the world of AI is that the city is home to leading experts in both approaches – and that makes Montreal unique.

“We have some of the best expertise in the world in deep learning at Université de Montréal with Yoshua Bengio and his team, and we have some of the best expertise in the world in reinforcement learning at McGill with our group.” says Pineau. “There are places that have one or the other. Toronto is very strong in deep learning. There is a group in Edmonton that’s very strong in reinforcement learning. But there is no other place in the world that has the same concentration in both these areas.”

Bengio says that many of the most promising advances in artificial intelligence right now are the result of combining deep learning and reinforcement learning. The AI teams at McGill and U de M have forged a close relationship, he adds. “The synergy between the two groups is very important.”

Bengio is a driving force behind much of that synergy. He is the director of the Montreal Institute for Learning Algorithms, a leading centre for machine learning research based at U de M (Pineau, Precup and Cheung are all associate members). He is also the co-founder of Element AI, an incubator of sorts that fosters collaborations between businesses and many of the city’s top AI researchers (Pineau, Precup, Cheung and their departmental colleague Gregory Dudek, a leading robotics expert, are all part of Element AI’s faculty fellow network). Element AI recently attracted more than $135 million from Microsoft, Intel and other investors.

If it seems that Bengio has his fingers in many pies, that’s largely by design. In interviews, he has expressed concerns over the prospect of having only one or two major tech companies play too dominant a role in the evolution of AI. “I want to remain a neutral agent,” he told Wired.

Building an ecosystem

For her part, Precup sees the arrival in Montreal of Facebook, Google and some of the other leading tech companies as an exciting development. “We need the ecosystem here to have lots of different players and I think part of the reason why Montreal is flourishing is precisely because some of the big names have come in. That sends a very strong signal that Montreal is a place to be and that we have a lot of talent in the city.

“Some of the people who are attracted here because of the big companies will eventually [create] startups,” adds Precup. “Ideally, what you want to see are a lot of choices. You want the big companies here, you want a positive environment for startups, you want universities to play important roles. People appreciate having a lot of options and that’s one of the things that makes Silicon Valley special. We’re starting to see that in Montreal. If you want to do [AI] research here, you can do it in a variety of different environments.”

Sometimes, having all those options available presents its own set of challenges. “It can be more difficult to keep [graduate students] focused on their thesis work,” Precup says with a laugh. “It’s like a buffet right now – all these interesting things [they] can try.”

It’s a big change from the way things used to be not so long ago, says Pineau. “Almost every one of my PhD students and post-docs would leave Canada and maybe two-thirds of my master’s students too. The students coming out of our labs today, many of the best ones, are staying in Canada. They’ll come into my office and talk about applying for different things in Montreal. That just wasn’t happening a few years ago.”

Bengio, the recent recipient of the Prix Marie-Victorin, Quebec’s top prize for research in pure or applied sciences, spent quite a bit of time in McGill classrooms and labs himself, earning three degrees from the University on his way to becoming, in the words of the host of Quebec’s popular TV show Tout le monde en parle, “un méga rock star!”

“My undergraduate degree in electrical and computer engineering provided a rather good mathematical basis for the kind of research done with machine learning,” he says. “I actually discovered artificial neural networks when I was looking for my [master’s topic], discovering a passion that continues to this day.”

LeCun believes that many major universities were slow in responding to recent developments in AI. “Some of the more conservative schools completely missed the boat on this,” he told his Montreal audience in October. “Some of the best-known names in the U.S. are falling behind a little bit. They’re trying to catch up now.” The universities that are currently excelling in AI “are the ones that took a chance and invested in this area – that includes the Université de Montréal, that includes McGill.”

One of the hottest areas in AI research right now is natural language processing (NLP), which uses AI methods to help machines master the nuances of human language. It’s a focus for much of Jackie Chi Kit Cheung’s research and one the reasons why RBC Borealis AI was keen on bringing him on board. While NLP has come a long way – think Siri or Alexa – it still has its limitations.

“My work on natural language processing focuses on trying to connect the structure of language to the structure of the world around us,” says Cheung. It’s one thing for a computer system to absorb all the intricate rules of a language’s grammar and quite another for it to use that language in a real world fashion where context can be tricky.

“You can think of it as giving [the machine] some kind of common sense knowledge to fill in more of the blanks that people just assume that other people know,” says Cheung. “But you can’t see [common sense usage] directly in the text that we deal with. Instead, it has to be inferred. And that’s a big challenge.”

Much of the research pursued by both Pineau and Precup relates to health care.

Pineau’s SmartWheeler project, which involves partners from U de M and three rehabilitation centres, is developing a robotic wheelchair that uses deep learning and reinforcement learning methods to achieve an end result that’s somewhat similar to self-driving cars.

“The wheelchair has a lot of sensors,” says Pineau. “It has lasers that give the position of all the obstacles around it. It has GPS. We’re particularly interested in the problem of driving through crowds. If there are a lot of people moving around, how do you get the wheelchair to choose a [safe] path?”

Operating a wheelchair is often no easy task, says Pineau. “It can be a burden in terms of fatigue. It can be a burden in terms of achieving very precise maneuvering in tight spaces. Whereas, if the AI system takes over and you’re just being driven around, you can have a lovely chat with whoever is accompanying you.”

Precup collaborates with neurology and neurosurgery professor Douglas Arnold, BSc’72, and electrical and computer engineering professor Tal Arbel, BEng’92, MEng’95, PhD’00, on a project that uses medical image analysis to detect and track the progression of biomarkers related to multiple sclerosis. “It’s using deep learning methods for analyzing brain imaging data,” says Precup.

Precup is also partnering in a project with McGill University Health Centre researchers that examines one of the most delicate and difficult decisions that needs to be made involving premature babies in neonatal intensive care units – when to extubate and allow the babies to breathe without mechanical assistance.

If you do it too soon, you end up having to reinsert the tube – and that’s not a pleasant procedure. But leaving the tube in place for too long carries risks of its own. “We’re looking at all the cardiorespiratory data and all the clinical variables that are recorded in the babies’ charts. We’re collecting this data [to come up with] temporal models that can predict the probability of a baby succeeding if they were extubated,” says Precup.

For all the progress that has recently been made in AI, Bengio says he is wary of some of the sci-fi hype that surrounds his field.

“AI is not magic,” says Bengio. “We are very far away from human-level AI and Terminator scenarios are not grounded in the current science of AI.” Speaking to his McGill audience in the fall, Facebook’s LeCun concurred. “We don’t even have the basic principles to build machines that are as smart as a rat, let alone a human.”

Still, there is no disguising the fact that AI has already begun to transform the technological landscape.

“Some companies have invested massively in AI research, but the majority of good ideas still come from academia,” said LeCun. “Many of them from here, from Montreal.”