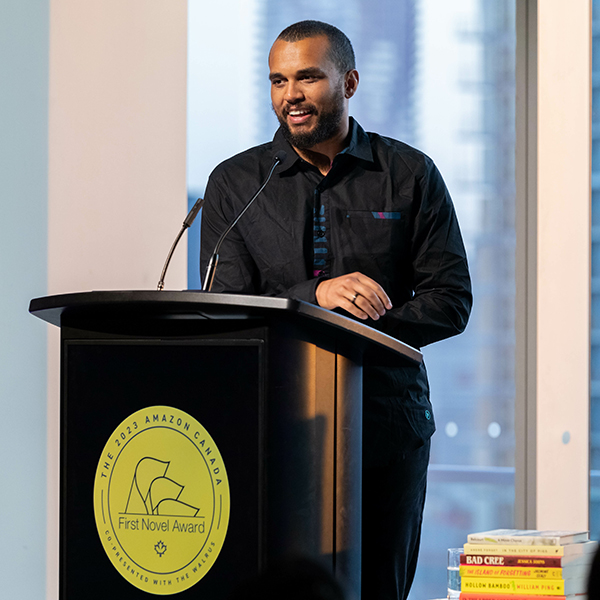

When technology ethnographer Alex Rosenblat graduated from McGill in 2010, there was no way she could’ve predicted she would wind up spending four years of her life researching Uber for a book – after all, the car hailing app only went live in its hometown of San Francisco that same year. Since then, of course, Uber has exploded into a worldwide phenomenon both praised as a technological innovator and criticized as a cutthroat lawbreaker.

Even though she now lives in New York, where she’s a researcher at the Data and Society Research Institute, Montreal plays a role in Uberland: How Algorithms are Rewriting the Rules of Work. Rosenblat, BA’10, looks at the long-term impact of Uber’s business practices and how it has changed society’s view of employment. Regardless of one’s opinion of Uber, there’s no denying the company has had a major impact this decade.

Because Uber’s evolution has been different in every city, Rosenblat did an exhaustive amount of research to get the full story: she logged more than 5,000 miles with Uber drivers across the United States and Canada, interviewed 125 of the drivers, and spent hours on online message boards frequented by drivers. She says Uber’s uncanny ability to adapt itself in each market and situation is a reason for its huge success.

“The relationship drivers had with Uber in New York would be vastly different compared to Montreal,” says Rosenblat. “I was in Montreal … before and after [Uber] became legitimate, so it ended up being really useful.” In New York, where Uber was already well established, drivers griped about the low pay, but in cities where the company was trying to gain a foothold, like Montreal, drivers spoke glowingly about how supportive Uber could be – footing the bill for impound fees, for instance.

“It was remarkable to see Uber’s tactics in one city compared to another,” says Rosenblat. “It was like whiplash.”

What Rosenblat discovered is that the story of Uber isn’t simply one of good and evil, or about a technology company that says it isn’t in the transport business and its drivers are not employees but entrepreneurs – it’s a complicated web involving drivers, passengers, governments and regulators with a variety of motivations.

“That’s a big part of the Uber story: There are always multiple audiences listening to the story Uber is telling. It turned technology reporters into labour reporters. Uber drivers became the face of the future of work because they were emblematic of the power of technology to impact society.”

While the job is presented in a positive light by Uber’s marketing department, the reality is 68 percent of drivers don’t last beyond six months. It explains why the company avoids adhering to typical transport company regulations in the cities it operates in – Uber needs to hire drivers quickly and frequently.

“Although Uber narrates itself as being a very hands-off employer, what I was able to observe over four years of research with drivers was that they’re actually monitored in much more granular ways than even a human supervisor would achieve,” Rosenblat says. “If a driver’s phone is shaking, they’ll be notified to make it more stable. If they brake too hard, they’ll get a notification. They also get notices about real-time and predictive demand. In reality, drivers are getting a constant flow of communication, and part of it is responsive to their own behaviour and part of it based on recommendations.”

With so many Uber drivers on the road, Rosenblat found many who weren’t motivated simply by money. She came across retirees who were bored and even one driver in Los Angeles who did it to unwind from their day job of working with PTSD sufferers. Some attempted to drive for Uber full-time, while many just used it to pick up extra bucks. Compared to other types of low-paying work – fast food restaurant jobs, for instance – drivers tend to regard their Uber work as a “good bad job.”

Another source of appeal for Uber among its drivers is that it’s a relatively easy way to make money – all you need is a car and a smartphone. Airbnb is another example of something that anyone with a home can do: rent it out for extra money. Of course, these “jobs” offer little in the way of security or benefits.

Governments and regulators have discovered that Uber can be a tough company to deal with. Rosenblat points to one dispute in Austin, Texas, where city officials wanted prospective drivers to have their fingerprints run through an FBI database. Uber resisted, arguing it already did its own background checks and that the fingerprint demands were excessive. When push came to shove, Uber simply switched off the app. “A factory couldn’t just pack up and leave [a city] in one second,” says Rosenblat.

Uber recently returned to Austin after state legislators took over the regulatory role and effectively quashed the fingerprint requirement.

“Drivers don’t have an employee handbook when they start out: instead, they learn what the rules are over time through hundreds of text messages, emails, and in-app notifications,” Rosenblat writes in Uberland. “Drivers are always playing catchup to Uber’s iterations.”

Those iterations are in constant flux as Uber’s algorithms experiment with different pay rates and features, notes Rosenblat. As she put it in a recent interview with Forbes, “Experimenting with someone’s livelihood isn’t the same as experimenting with recommendations for romcoms on Netflix.”